We are happy to feature an excerpt from Mikhail Goldis’s Memoirs of a Jewish District Attorney from Soviet Ukraine (Academic Studies Press, 2024), translated by Marat Grinberg, professor of Russian and humanities at Reed College and Goldis’s grandson. Grinberg’s previous book was the highly informative The Soviet Jewish Bookshelf: Jewish Culture and Identity Between the Lines (Brandeis University Press, 2022). The Soviet Jewish Bookshelf makes the original argument that, in the anti-Semitic Soviet Union, Jews circumvented the proscriptions on public expression of Jewish identity “through their ‘reading practices'”: they built up home libraries of books on Jewish subjects, which, given “the heavy censorship of Jewish content,” they often had to read “between the lines” (the citations are from my review). Olga interviewed Marat about his book, and you can listen to their rich conversation here, which includes reading suggestions of the various writers the book discusses.

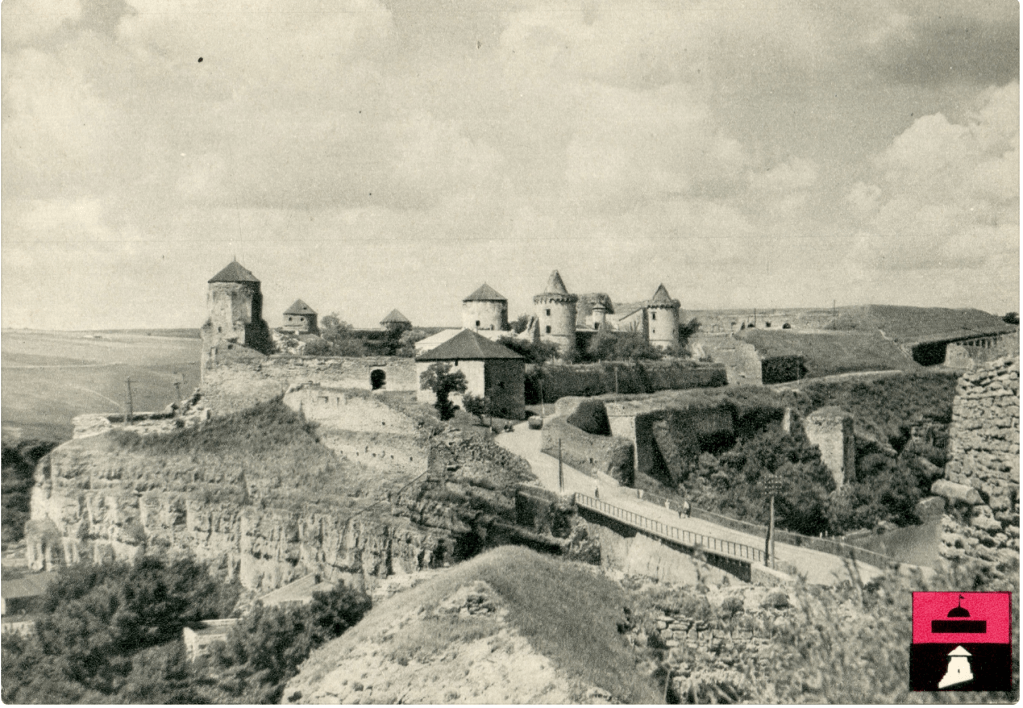

Originally written in Russian after Goldis immigrated to the United States, Memoirs of a Jewish District Attorney from Soviet Ukraine is his account of working as a detective and district attorney in the post-war years, first in Krasyliv and then in Kamyanets-Podilskyi. As Marat notes in his Introduction, his grandfather’s memoirs demonstrate “what it took for a Jewish attorney to survive in the halls of Soviet power.” Performing the difficult balancing act between representing the state and remaining true to oneself, his grandfather emerges as a deeply principled man striving for justice. In a society that valorized the collective, “[w]hat mattered to him were the individuals caught up in life’s contingencies. In this respect, he reminds me of Georges Simenon’s inspector Maigret or Peter Falk’s Columbo.” These references to famous fictional detectives are well placed; recounting Goldis’s various cases, this book will appeal to fans of true crime, as well as to those interested in Soviet-Jewish experience(s).

The excerpt below, from the chapter “Seven Forty,” shows Goldis at work, battling Soviet anti-Semitism to get to the truth.

Seven Forty by Mikhail Goldis (translated by Marat Grinberg)

Many years ago I fell in love with a dance melody I heard for the first time at a Jewish wedding. They call it “Seven Forty.” A strange name, isn’t it?

In 1974, I worked as a deputy district attorney in Kamyanets-Podilskyi. Among my responsibilities was representing the district in court. One time, I was preparing a hearing pertaining to malicious hooliganism. An inebriated young man had assaulted patrons in a restaurant without any reason. The evidence was rock solid: we had the testimony of victims, witnesses, medical experts, and, finally, the perpetrator’s admission of guilt under the burden of indisputable facts. Everything was crystal clear, except for one detail . . .

I turned again to the man’s biography: Mikhail Khanukovich, twenty-one years old, a student at a construction community college and, as printed on the infamous fifth line in his passport—a Jew. I was flummoxed. In all these years, I’d come across many types of hooligans; they were usually uneducated and primitive people. This was the first time I’d seen a Jewish man of this unfortunate type. Khanukovich’s victims were also hardly ordinary—they were well-known and respected people in town. One of them, Faraonov, was the head of the local committee of culture; and the other was Kazimirchuk, a director of a pharmacy. Both were, of course, members of the party. Khanukovich was tried by the district court and his prospects looked very grim—he was facing a sentence of four or five years in prison.

[…]

The court proceeded to question the victims. They were both of average height and muscular. Studying them, I wondered how the puny Khanukovich had managed to overpower these strong fellas. Their testimony was precise and reserved, as one would expect from such important people. They’d stopped at the restaurant for a drink after a long day at work. While Faraonov, the culture boss, was talking to the conductor of the restaurant’s orchestra about an upcoming performance at a nearby kolkhoz, the drunk Khanukovich charged at them, knocked Faraonov down with a fist to his face, and then clobbered Kazimirchuk who had rushed to help. The police were called and the delinquent was pacified.

The judge gave Khanukovich an opportunity to admit his guilt, but he declined and proceeded to tell his side of the story. He and a bunch of other students were at the restaurant, celebrating the end of final exams. Khanukovich went up to the conductor and asked him to play “Seven Forty.” With slight irritation in his voice, the judge interrupted the defendant. “What does ‘Seven Forty’ mean?” he asked. Khanukovich said it was a Jewish dance and continued his testimony. When he asked to play this dance, Faraonov, who was standing nearby, said to him: “You dirty Jew—you should move to Israel where they’ll play your Yid dances for you.” In response, Khanukovich struck Faraonov, and then whopped Kazimirchuk, the cavalry.

[…]

As the court questioned the witnesses—the restaurant’s musicians, waiters, patrons—none of them mentioned the conversation between Khanukovich and Faraonov. Indeed, it could very well have been that they simply hadn’t heard it. There was one witness, though, who couldn’t make the same claim: the conductor who had been talking with Faraonov right before Khanukovich hit him. He needed to state unequivocally that the conversation had or had not taken place.

The judge understood full well the significance of this testimony. He seemed perturbed. I had never discussed antisemitism or anything Jewish with him and could only guess what his feelings on the matter might be. I did know, however, what the government’s official position regarding this matter was: there was no antisemitism in the Soviet Union; any statement to the contrary was Zionist and imperialist slander. Thus, as I’d learned from other cases, antisemitic incidents could never be mentioned in official proceedings. This was the reason for the judge’s distress. A representative of the state, he had to live up to his stature and question this crucial witness himself.

[…]

To find out the outcome of this case and to read about Goldis’s other cases, please buy Memoirs of a Jewish District Attorney from Soviet Ukraine and tell your local and/or university library to carry it.

Marat Grinberg immigrated to the United States from Ukraine in 1993, graduated from the joint degree program between the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and Columbia University in New York City in 1999, and received his PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Chicago in 2006. A scholar of Jewish and Russian literature and culture, and of cinema, he is a Professor of Russian and humanities at Reed College. Grinberg’s latest book, published by Brandeis University Press’s Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry, is The Soviet Jewish Bookshelf: Jewish Culture and Identity Between the Lines. He is also the translator and editor of the just published Mikhail Goldis, Memoirs of a Jewish District Attorney from Soviet Ukraine. Marat Grinberg’s most recent essays have appeared in Tablet Magazine, Mosaic, Los Angeles Review of Books, and Jewish Journal. He is currently writing a book about Jewishness and the Holocaust in Soviet and East European science fiction.

Я заказал книгу!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Спасибо, очень рада.

LikeLike