When: March 6, 7:00 pm

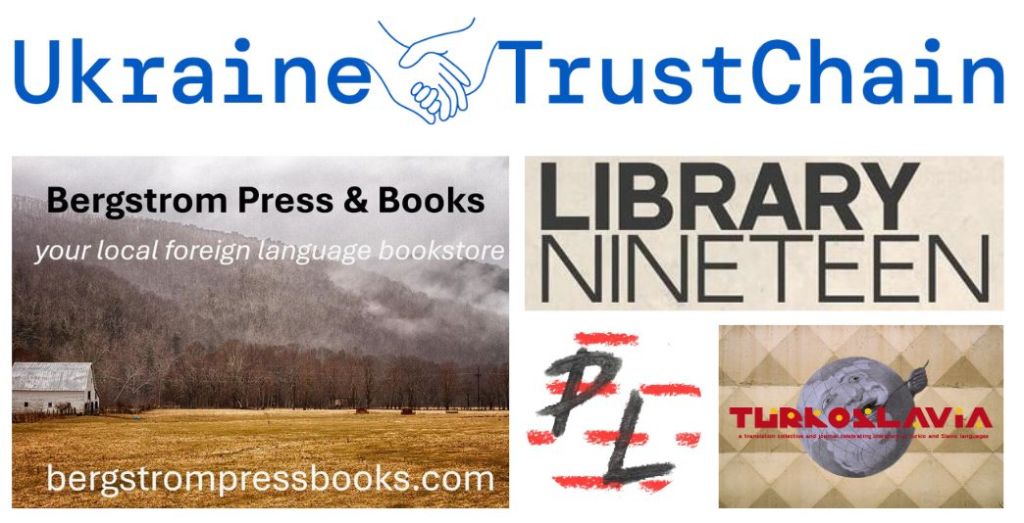

Where: Library Nineteen

606 S. Ann St, Baltimore MD, 21231

*** Please register on Eventbrite ***

This one-of-a-kind reading brings together writers from Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet countries who now make their homes across the United States. Taking place during the 2026 AWP Conference, the event celebrates a growing circle of poets, prose writers, and translators from complex, cross-cultural identities whose work is shaped by displacement and immigration, survival and resilience.

More essential than ever, nuanced storytelling is our compass toward understanding and community. Writing from and beyond histories marked by authoritarianism and censorship, the authors center free expression, creative freedom, and democratic dialogue. Through stories of reinvention, loss, and belonging, we build cultural and intergenerational bridges, reclaiming the power of connection and voice.

** This event is a fundraiser for Ukraine ** Free admissions ** Book sales by Bergstrom Press & Books ** Please register on Eventbrite **Arrive early to get a seat! **

This event is co-hosted by Turkoslavia, a translation collective and a journal celebrating literature in Turkic and Slavic languages.

* Thank you to Ena Selimović for designing the promotional materials

Featured Readers:

Alina Adams is the NYT best-selling author of soap opera tie-ins, figure skating mysteries and romance novels. Her Soviet historical fiction includes The Nesting Dolls, My Mother’s Secret: A Novel of the Jewish Autonomous Region and Go On Pretending. www.AlinaAdams.com

Born in the former Soviet Union, Valerie Bandura is the author of two collections of poems, Human Interest and Freak Show. Her poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, The Gettysburg Review, and Ploughshares, among others. She teaches writing at Arizona State University. https://valeriebandura.com/

Svetlana Binshtok is a writer and storyteller whose work has appeared in The Louisville Anthology, The Second City, 80 Minutes Around the World, and Fillet of Solo Festival.

Danya Blokh is a poet from Birmingham, Alabama. He received his bachelor degree in Comparative Literature and Russian from Yale University, and is now pursuing an MFA in Poetry at Johns Hopkins.

Katie Farris’s work has appeared in Poetry & The New York Times. Her latest book, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive (Alice James 2023) was shortlisted for the 2023 TS Eliot Prize. She co-translates from Ukrainian, including Lesyk Panasiuk’s Letters of the Alphabet Go to War (Sarabande 2026).

Katarzyna Jakubiak’s recent nonfiction collection is Obce stany (Alien States; Poland, 2022). She is also a short story writer, translator, scholar, and Associate Professor of English at Millersville University.

Victoria Juharyan teaches literature and philosophy at Johns Hopkins University. She has been writing poetry since she was three years old but first time she agreed to read her work in public was in 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, at a similar event during AWP. Consequently, her poems were published in Symposeum Magazine (https://api.symposeum.us/author/victoria/) and set to music.

Andrea Jurjević is a poet, translator, and painter from the Adriatic coast of Croatia. Her latest collection is In Another Country (2022 Saturnalia Books Prize). Read her Substack Lovesong to Elsewhere: https://andreajurjevic.substack.com/

Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odesa, Ukraine and lives in New Jersey. He is the author of Dancing in Odessa (Tupelo) and Deaf Republic (Graywolf) and translator & editor of many other books.

Julia Kolchinsky is the author of four poetry collections, most recently, PARALLAX (The University of Arkansas Press, 2025). Her next book, When the World Stopped Touching (YesYes Books, 2027) is a collaborative collection of letter-poems with Luisa Muradyan, written during the first year of COVID . She is Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Denison University.

Maria Kuznetsova was born in Kyiv, Ukraine. She is the author of the novels Oksana, Behave! and Something Unbelievable and is an Associate Professor at Auburn University. https://mariakuznetsova.com/

Ellen Litman is the author of two novels, The Last Chicken in America and Mannequin Girl. She teaches at UConn. Born in Moscow, she immigrated to the US in 1992.

Olga Livshin’s poetry appears in Poetry magazine, the Southern Review, and Ploughshares. She is the author of A Life Replaced: Poems with Translations from Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Gandelsman. olgalivshin.com

olga mikolaivna was born in Kyiv and works in the (intersectional/textual) liminal space of photography, word, translation, and installation. Her debut chapbook cities as fathers is out with Tilted House and “our monuments to Southern California,” she calls them is forthcoming with Ursus Americanus Press. She lives in Philadelphia and teaches at Temple University. https://www.olgamikolaivnapetrus.org

Asya Partan’s writing appears in The Boston Globe, The Rumpus, Pangyrus, NPR‘s Cognoscenti, and The Brevity Blog, and is forthcoming from Liberties. An MFA (Emerson College) and a memoir are in the works. www.asyapartan.com

Irina Reyn is the author of three novels: Mother Country, The Imperial Wife, and What Happened to Anna K, which won the Goldberg Prize for Debut Fiction. Her work has appeared in One Story, Ploughshares, Tin House, and other publications. She teaches fiction writing at the University of Pittsburgh.

Ena Selimović is a writer, translator, and co-founder of Turkoslavia, a translation collective and literary journal. Her work has appeared in Words Without Borders, The Paris Review, and elsewhere. https://www.turkoslavia.com/

Lucy Silbaugh is an MFA student in poetry at Johns Hopkins. Her poems have appeared in the TLS and Gulf Coast and are forthcoming in the The Iowa Review and The Bennington Review. She has published essays on Nabokov, Gazdanov, and Henry James.

Lana Spendl’s work has appeared in The Threepenny Review, World Literature Today, The Rumpus, and other journals. She is the author of a chapbook of fiction and reads for Crab Creek Review. Her childhood was divided between Bosnia and Spain prior to her immigration to the States. Read her work at lanaspendl.com/writing.

Alina Stefanescu is a unique poetic voice of the Romanian American diaspora. Her poetry collection Dor won the Wandering Aengus Press Prize (September, 2021). In the collection, My Heresies (Sarabande, 2025), she has “translated” Romanian childhood myths into the present as spaces for ontology.

Natalya Sukhonos is a poet who was born in Odesa, Ukraine and now lives in Upstate NY. She is the author of Sunlight Trapped in Stone (Green Writers Press 2026) and two other collections. natalyasukhonos.com

Vlada Teper is a writer and educator from Moldova. Her work has appeared in Newsweek, NPR, World Literature Today, and others. She is the founder of the nonprofit Inspiring Multicultural Understanding. www.vladateper.com

Katherine E. Young is the author of Day of the Border Guards and Woman Drinking Absinthe and served as the inaugural Poet Laureate of Arlington, VA. She translates Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Russian, and Ukrainian writers. https://katherine-young-poet.com/

Tatsiana Zamirovskaya is a bestselling Belarusian author who writes metaphysical and socially charged fiction. She is the author of three short story collections in Russian and two highly acclaimed novels, The Deadnet and Candles of Apocalypse. She worked for Voice of America as an editor and journalist until its shutdown in March 2025.

Olga Zilberbourg is the author of LIKE WATER AND OTHER STORIES (WTAW Press). She co-facilitates the San Francisco Writers Workshop and co-founded Punctured Lines, a blog about literatures from the former USSR. https://zilberbourg.com/

Lena Zycinsky is a Belarusian-American poet and artist, working across languages and disciplines. The author of several poetry collections and art exhibitions in Russian, Lena holds an MFA from New York University. Her work has been published in the New York Times and selected for the Poetry Archive. Born in Minsk, Lena has lived in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Greece, and is currently based in London. More at: www.lenazycinsky.com