Avdotya Panaeva was born in 1820 and first began publishing her work in one of Russia’s premier literary magazines, Sovremennik, in 1846. The author of numerous short stories, novels, memoirs, as well as collaborative projects, she has only recently begun to achieve the recognition that she deserves in the English-speaking world.

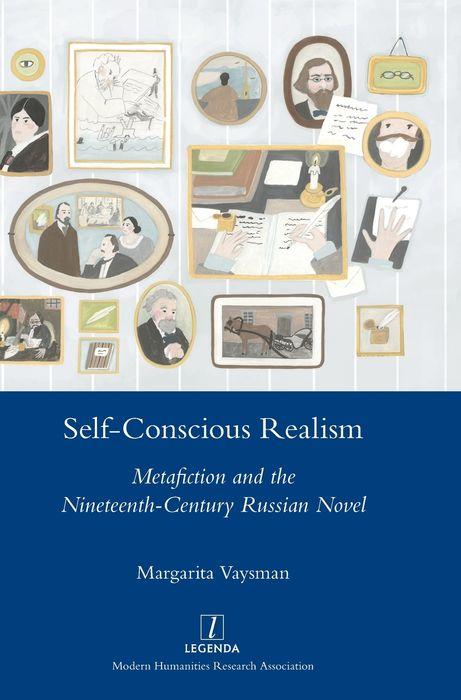

On October 8, 2024, Columbia University Press published Fiona Bell’s translation of Panaeva’s first novel, The Talnikov Family. This became the second full-length translation of Panaeva’s work to English. In my review of the book in On the Seawall, I mention several social and historical factors that have kept this delightful novel from English-language readers for so long. In writing about this book, I have relied, in part, on Bell’s introduction to the novel and on the research by Margarita Vaysman, whose book Self-Conscious Realism: Metafiction and the Nineteenth-Century Russian Novel devotes a section to Panaeva’s work, including an excerpt that ran in Punctured Lines.

Today, it is my pleasure to discuss this novel and Panaeva’s work more broadly with her translator Fiona Bell and scholar Margarita Vaysman.

Olga Zilberbourg: How did you first discover Panaeva’s work and what attracted you to it?

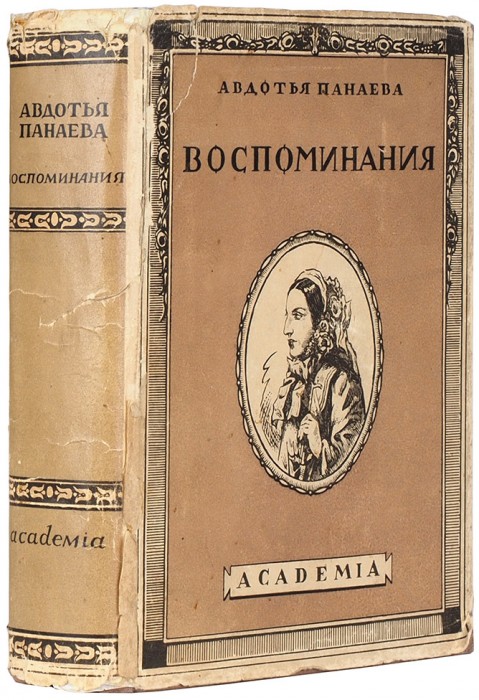

Margarita Vaysman: I grew up and went to school in Russia, and excerpts from Panaeva’s most famous book, her Memoirs (1889), are often assigned as secondary reading in high school. They are considered essential for understanding the historical and social backdrop for classic nineteenth-century prose and poetry, like Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Children (1862) or poems by Nikolay Nekrasov, Panaeva’s romantic partner of many years. Panaeva is far from being forgotten in Russia: unlike many other female novelists, her Memoirs, to my knowledge, have not been out of print since their first publication in the 1920s, with the latest edition available this year from several publishers. Hers is a rare female voice in the predominantly male chorus of other big nineteenth-century Russian writers. I have been intrigued by her work ever since my first encounter with it.

Fiona Bell: I discovered Panaeva much later than Margarita did! In a graduate seminar on Russian Romantic Poetry, I became interested in Nekrasov’s poetry as a liberal genre of seduction, poems that encourage their woman addressee to embrace the principles of “free love.” When I realized that these poems were written to Panaeva—a figure unknown to me—I became curious about her perspective and was thrilled to find that she had also been a writer. I read The Talnikov Family and Panaeva’s Memoirs pretty torridly—I was so taken with her voice. Around then, I also enjoyed Joe Andrew’s translation of Panaeva’s novella, The Lady of the Steppes.

Olga Zilberbourg: Panaeva comes from a family of theater actors and was trained as a ballerina. At the same time, many commentators note the influence of George Sand (first translated to Russian in 1832 and attaining great popularity there) on her fiction. How do these disparate threads of her background combine—or clash—in her work?

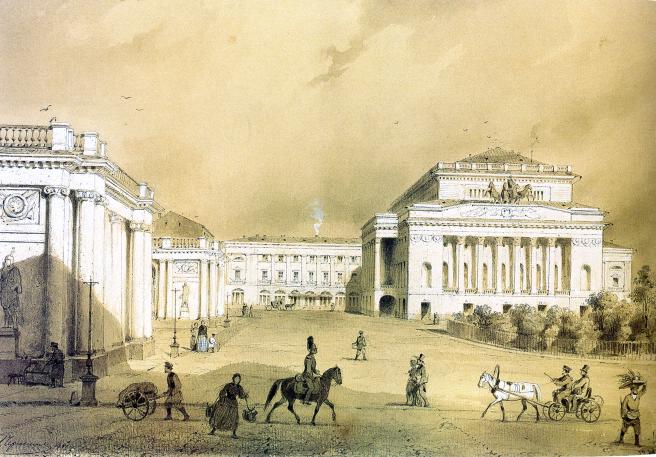

Margarita Vaysman: Panaeva’s theatrical family was at the top of their professional hierarchy, because of their employment at the Imperial Theatre. So it is not at all surprising that a young woman from this background would be familiar with “trendy” literary fiction. We also know that she was assisting her husband, Ivan Panaev, a minor writer and an influential journalist, with hosting his literary salon, famous in St. Petersburg society. Having married early (just like Natasha in The Talnikov Family!), Panaeva would have benefitted from being a member of an intensely intellectual, literary environment at a crucial time of her own intellectual and emotional development as a young woman: many of her experiences at the salon are described in detail in the Memoirs. Panaeva is indeed sometimes referred to as the “Russian George Sand,” perhaps because of her open polemic with this writer in novels like A Woman’s Lot (1862). In fact, Panaeva’s own political leanings were much more conservative and the thrust of her feminist argument was, in a way, against Sand as a proponent of free love. In A Woman’s Lot, Panaeva offers a passionate denunciation of the fashion for female emancipation “in name only”: a kind of a new moral order in which women were, first, encouraged to disregard social norms of gendered behavior but were then left with no support in case of any consequences, like bearing illegitimate children or falling victim to disease. In the cluster of articles “Avdotya Panaeva by Herself: Subjectivity, Narrative, Plot” that I co-edited for the Russian academic journal NLO in 2023 with Pavel Uspenskii and Andrei Fedotov, you can find their excellent article on Panaeva’s polemic with her male colleagues on these topics.

Olga Zilberbourg: The Talnikov Family is told from the perspective of a rapidly growing young woman. We get to witness Natasha’s development starting from about six years old to about sixteen, when she marries and leaves her parents’ home. The narrative style of the book felt extremely contemporary to me, the voice of the young narrator instantly captivating. What were the challenges of capturing this voice in English, Fiona?

Fiona Bell: Until I started The Talnikov Family, I had only translated works by millennial women. This wasn’t intentional but, for better or worse, I found that I could use my own voice—with its U.S. millennial syntax, lexicon, and idioms—when translating these works. Because of our temporal distance, however, Panaeva was a new challenge. I wanted to give a sense of the 1840s to the anglophone reader, so I read Charles Dickens, George Sand, and Charlotte Brontë while working on the translation. At the same time, I wanted the simplicity and immediacy of the children’s voices to come through. Dickens and Brontë were helpful models on this front because they feature so many children characters. Drama is also helpful for translating dialogue of another era: I read translations of Turgenev’s A Month in the Country and Ibsen’s plays. Translators of drama are so good at preserving the historical quality of the language while also prioritizing the language’s readability, since they usually have contemporary actors in mind. Often, by imagining an actor doing a monologue as Natasha, I was able to focus on making her voice feel immediate.

Olga Zilberbourg: Margarita, what do you find particularly noteworthy about Natasha’s voice in this novel? She tells the story in the first person, sticking fairly closely to only recounting the events that she has experienced directly or has been a witness to. Once in a while, when Natasha recounts what has happened to her siblings, we know that she couldn’t have witnessed the scene directly, but even then she sometimes indicates the circumstances under which she received the knowledge that she’s recounting. How does this narrative style compare and contrast with the work of her contemporaries?

Margarita Vaysman: I think the most interesting thing about Natasha’s voice in this novel is that she speaks not just for herself, but also for others. As Jane Costlow, a scholar of Russian literature, once pointed out, Natasha becomes almost a disembodied voice of general suffering in the novel. This type of narration might appear more “modern” than it should, but in fact Panaeva’s style is fairly typical for the period in which she was writing. This particular feature of the narrative voice is partly a result of common use of free indirect speech in nineteenth-century Russian prose—to an anglophone reader, this narrative style seems very modern, reminiscent of authors like Henry James, who paved the way for its wide use in the English novel. The grammatical structure of Russian, on the other hand, means that this narrative technique is indeed very common in the second half of the nineteenth century, and an obvious comparison here would be the novels of another major woman writer of the time, Nadezhda Khvoshchinskaia—many of her works are now available in English and more information can be found in the digital collection hosted at the at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Olga Zilberbourg: Margarita, in your book Self-Conscious Realism: Metafiction and the Nineteenth-Century Russian Novel, you argue that Panaeva’s later novel, A Woman’s Lot “did not conform to the generally held perceptions of how a realist novel should function discursively and had therefore sped up her disappearance from the canon.” Do you find The Talnikov Family similarly disruptive to expectations? Why or why not?

Margarita Vaysman: Great questions! The Talnikov Family as a text is indeed very different from A Woman’s Lot in many ways. Structurally, it flows differently, because, as far as we know, it was not intended for serialization, or at least if it was, then not in as many installments as A Woman’s Lot (most Russian novels of the second half of the nineteenth century were serialized first, and only then published as a separate edition). Stylistically, it’s more polished because Panaeva was working on it before she became, in essence, an assistant editor of Sovremennik and had to produce a steady stream of “filler” prose. One of the leading Russian literary journals of the time, Sovremennik was run by the poet Nikolay Nekrasov and Ivan Panaev, Panaeva’s husband, but the data we have suggests that she was at least a managing editor, if not a literary one. So some of her later texts were very obviously produced to fill in the gaps left in the journal very shortly before publication deadlines by overzealous censors, who would often ask the editors to remove up to 30% of each volume’s content. This means that the texts were often rushed to the printers without much literary editing. The Talnikov Family is also Panaeva’s most autobiographical work: it’s very personal and, as some critics have called it, “raw.” In my article on Panaeva, published in Russian Review in 2021, I argue that, after the novel was banned for “undermining parental authority,” Panaeva learned her lesson: her later fiction is much more toned-down, and often “hides” a subversive argument in so many plot twists that you can imagine the censors giving up halfway through just because they could not follow the overly complicated story!

Olga Zilberbourg: The Talnikov Family is a powerful exposé of corporal punishment that was deemed acceptable in the Russian Empire in the middle of the nineteenth century. The censor deemed the book “immoral” and cancelled it with the formula: “I prohibit because of its immorality and undermining of parental authority.” Can you speculate what aspects of the book particularly offended his sensibilities?

Margarita Vaysman: Two things are very important to remember here: firstly, that corporal punishment (and to an extent, bodily autonomy in general) in nineteenth-century Russian society was not just an issue of age and gender, but also of class—only those who were exempt from the Russian version of poll tax, podushnaia podat’ (noblemen, priests, etc.), were protected from it. So I think in this novel corporal punishment becomes, in a way, a symbol of the general lack of bodily autonomy for the majority of the citizens of the Russian Empire—you can easily see how the censors would have perceived it this way. Secondly, we should not forget that corporal punishment was extremely common not just in Russia but also in many European countries up until WWII, so this is hardly a nineteenth-century problem. I would say it has never really become unacceptable in most post-Soviet societies even now: a small minority of educated, primarily urban parents are, and have been, for a long time, aware that physical violence does not exactly produce the best pedagogical results, but for the vast majority, corporal punishment still remains an essential part of parenting.

Olga Zilberbourg: In Fiona’s introduction, she notes that “Panaeva, a true citizen of the nineteenth century, recognizes the imbrication of all the age’s ‘questions’: the woman question, the labor question, the serfdom question, and others.” I was particularly fascinated by Panaeva’s representation of two of these questions. First, alcoholism and addiction, and particularly female alcoholism and addiction. Natasha’s grandmother is a full-blown alcoholic, and her mother is addicted to gambling. Paradoxically, their addictions complicate their character (without her passion, the mother in particular might have appeared cartoonishly evil) and portray them as possessing quite a bit of agency in the household. How common is the representation of female addictions in contemporaneous literature? What do you think was important for Panaeva in her depictions of the mother and grandmother?

Margarita Vaysman: Here, Panaeva is following the fashionable literary style of the “physiological sketch”—a style of realist writing, influenced by nascent social sciences like anthropology, ethnography, and urban sociology. The difference here is that in this novel it becomes almost an autoethnography, describing a family very much like her own. What I find fascinating is that Panaeva avoids slipping into the narrative mode of Gothic realism, which often dominates these kind of descriptions—a good example here is the very dark nineteenth-century novel The Golovlev Family (1880) by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. Both Panaeva’s and Saltykov-Shchedrin’s texts can be seen as early examples of the style of “chernukha” writing that is familiar to contemporary readers from the works of by now canonical twentieth-century writers like Liudmila Petrushevskaia. As the scholar Kirill Zubkov points out in his work on nineteenth-century Russian literature and theater, “drunken old woman” is a common comical type in Russian theater, so perhaps this is what gave Panaeva an idea for this character. We can also find a vivid portrayal of gambling addiction in Dostoevsky’s The Gambler.

Fiona Bell: So interesting, Margarita! The mother’s and grandmother’s voices were difficult to translate, probably because they exist between genres. I had so much fun translating the chapter when the grandmother tells Natasha about her horrible encounters in youth, including run-ins with a lecherous landlord and a bumbling thief. Now that you mention it, Olga, her speech does have a drunken quality: she repeats herself often and has wild swings in tone. By contrast, the mother character is a striver who attempts high society expression and embodiment. As I translated her speech, I imagined her as someone who grew up with the grandmother and grandfather, and perhaps retains their idiomatic sensibility, but who also tries to speak the language of the elite. Sometimes her hybrid speech can have comedic effect—just one example of Panaeva’s satirical genius.

Olga Zilberbourg: I’m also interested in Panaeva’s portrayal of the “Jewish question.” In the novel’s seventh chapter, the family servant Luka recounts a tale from his time of service during the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812. In the story, a Jewish girl gets taken in by a military commander and refuses to kiss his hand. He then forces her obedience, but she continues to fight for her independence. In protest, she first tries to hang herself, and when that plan backfires, escapes by cutting the master’s throat. Though this episode does conform to Russia’s racializing discourse, as you point out in the comments, Fiona, and portrays the Jewish woman as a wild Other, I thought that the story had a lot of revolutionary potential in the way it was presented. The Jewish woman succeeds in escaping the law and her would-be master, and isn’t this what Natasha herself is trying to do, escape the confines of patriarchy? Reading the novel, it struck me that the Jewish woman serves almost as a role model for Natasha, as an inspiration to never give up her fight against enforced expectations. I’d love to know how you two interpret Panaeva’s insertion of this episode into the novel.

Margarita Vaysman: I think your reading of it is close to mine: the point Panaeva is making is that there are no role models in Natasha’s immediate circle, and, if she did not use her capacity for imagination, she would not have seen a possible way out of her abusive family situation (although, ironically, we have no way of knowing how happy her future marriage will be! Natasha is exchanging one form of dependence for another).

Fiona Bell: This passage is such a key to the novel. As I write in the introduction, Panaeva beautifully suggests the imbrication of various systems of violence: serfdom, imperialism, and patriarchy. For me, the main interpretive flashpoint is the end of the chapter. After the servant Luka finishes telling the story, we return to the frame narrative when Natasha notes on behalf of her siblings: “We had trouble falling asleep that night and had terrible dreams.” Where, for these children, is the terror of this story? Are they empathizing with the Russian gentry officer or the Jewish girl? Or both? I think this ambivalence is at the heart of Panaeva’s project: empathy is not a straightforwardly virtuous emotion. It’s a very confusing emotion, in fact.

Olga Zilberbourg: The Talnikov Family was first published in 1927 by a beloved and in many ways pioneering Soviet editor and critic Kornei Chukovskii, who, however, did a terrible disservice to Panaeva by accompanying the publication with his own essay questioning Panaeva’s abilities and her authorship of the novel (Chukovskii believed that the novel was likely co-authored with Panaeva’s lover Nekrasov, for which there is no textual evidence). The damage of his accusations effectively acted as another way of censoring it; it prevented Panaeva from being considered as an equal in the literary community. How do we evaluate that kind of advocacy today? Would the novel have fared better or worse had Chukovskii not taken it up then?

Margarita Vaysman: This is a very interesting question, because Chukovskii also re-published Panaeva’s Memoirs around the same time, and they were, and remain, hugely successful and popular among Russian readers even now. The Memoirs were also accompanied by a foreword, which was written in a very similar style. So Chukovskii’s framing, per se, could not have damaged the perception of this novel too much—otherwise why would the Memoirs not have been affected by it? Chukovskii has also famously led a campaign, full of misogynist ranting, against a popular children’s writer, Lidiia Charskaia, and yet we have seen a “return” of Charskaia in the 1990s. I think the larger issue here is the general perception of what a nineteenth-century Russian novel should and should not be: the kind of raw descriptions of physical and emotional suffering that Panaeva includes in this text are unsettling for two reasons. Firstly, because they are related in a female voice and secondly, because these kinds of descriptions, at the time of writing, belonged to a shorter form of prose, often marked as “documentary” —the sketches. So when decades later Dostoevsky’s characters discuss raping adolescents, this is somehow more acceptable stylistically to readers because the novelistic form had developed since then to incorporate these formerly semi-documentary forms of writing and, because, of course, they are all men. So to me, the lack of success of The Talnikov Family upon publication in 1927 has more to do with its intrinsic qualities (like style and topics that it engaged with) than with Chukovskii’s framing of it: it is, in many ways, not at all a text that you imagine when you think of a nineteenth-century Russian novel. This is what makes it so interesting for us today, but for readers in the 1920s, looking for easily digestible descriptions of the “horrors of the tsarist past,” this would have counted very much against it.

Fiona Bell: It’s also worth thinking about how we continue to evaluate women’s literary narratives about violence. When I pitched this book, it was natural to advocate for its publication by suggesting its place in the vaunted canon of nineteenth-century Russian novels. But The Talnikov Family also logically sits within a longer and larger canon of women writing their difficult childhoods. In fact, the first book I translated, Nataliya Meshchaninova’s Stories of a Life (an excerpt from that book appeared in Punctured Lines; editors), also happens to be about a girl named Natasha who’s narrating a violent childhood with wit and anger. More recently, books like Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy, Tara Westover’s Educated, Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, and Ashley C. Ford’s Somebody’s Daughter have become bestsellers. I’m really interested in the factors that make readers today “buy into” (or, buy) a memoir: must the writer already be famous? Or is there something inherently compelling about this genre? And how are women writers sometimes pushed out of “literary fiction” and into “memoir” when they narrate trauma? The Talnikov Family is a wonderful case study for both these issues.

Olga Zilberbourg: Panaeva and her fellow female writers from the Russian Empire seem to have been the first victims of the world’s infatuation with “Russian literature.” They often acted as champions of the work of their male companions, while nobody returned the favor. I know today many people are working to rectify this situation. What initiatives in trying to uplift female authors of the past have been the most successful? What else would you love to see happen in our literary communities?

Margarita Vaysman: I would specifically recommend the Khvoshchinskie Project: you can read about it here https://khvoshchinskie.web.illinois.edu/.

Fiona Bell: Translators are great advocates of these nineteenth-century women writers. Recently published books include Karolina Pavlova’s A Double Life, translated by Barbara Heldt, and City Folk and Country Folk by Sofia Khvoshchinskaya, translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. But I would also encourage readers to lend their support and curiosity to writers today: gender inequality in reading and literary criticism is not, alas, a relic of the nineteenth century! Read Alisa Ganieva, Leyla Shukurova, Alla Gorbunova, Tatsiana Zamirovskaya, and other writers covered on Punctured Lines!

Olga Zilberbourg: I was amazed to learn from Fiona’s introduction that this was only the second full translation of Panaeva’s work to English. Which of her books would you love to see translated to English next?

Margarita Vaysman: Definitely the Memoirs. Her wonderful descriptions of St. Petersburg society, and, importantly, the women journalists and editors, are priceless, not to mention her very catty notes on Turgenev and Alexandre Dumas!

Fiona Bell: Like Margarita—and thanks to Margarita’s scholarship!—I am a fan of Panaeva’s later novel A Woman’s Lot. I would love to assign this work when teaching other novels of the 1860s, like Fathers and Children, What Is To Be Done?, and War and Peace. But I agree that the Memoirs would appeal to lovers of Russian literature and fans of memoir alike. This project is next on my list!

Fiona Bell is a writer and scholar from St. Petersburg, Florida. She has published English-language translations of the Russian filmmaker Nataliya Meshchaninova, the Belarusian writer Tatsiana Zamirovskaya, and other Russophone authors. She is completing a Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University, where she studies the Russian racial imaginary as it was elaborated in the nineteenth-century literary canon.

Margarita Vaysman is Associate Professor of Nineteenth-Century Russophone Literature and Thought and Fellow in Russian at New College, University of Oxford. Her research focuses on literary texts, primarily the Realist novel, and history of gender and sexuality. Her major publications include a monograph Self-Conscious Realism: and the Nineteenth-Century Russian Novel (2021) and two co-edited volumes: Nineteenth-Century Russian Realism: Society, Knowledge, Narrative (2020) and The Oxford Handbook of Global Realisms (2025).

Found this fascinating, thanks, as I really enjoyed the book!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for reading! I’m very much looking forward to reading the original, which I have checked out of our university library and will get to … at some point!! Glad you enjoyed the book; one of my goals is to read more 19th-century Russian women writers, since that century is so dominated by men.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading! Both Fiona and Margarita are so insightful. I really hope we will have the Memoirs in English before too long.

LikeLiked by 1 person