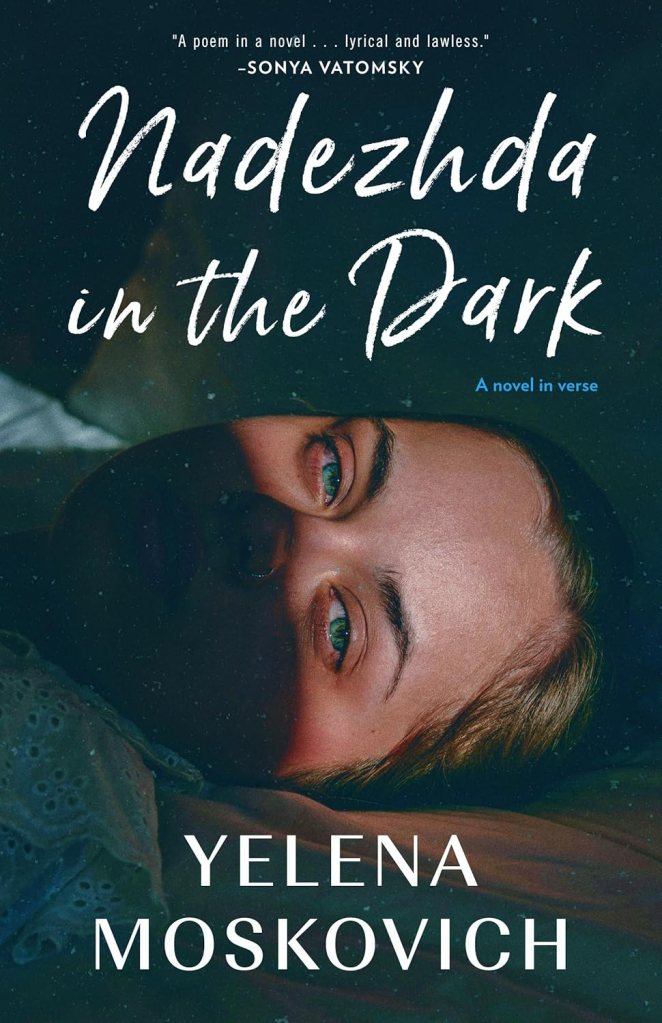

Today, in the US, we welcome a new book by Ukrainian-born American and French author Yelena Moskovich. Innovative Dzanc Books is bringing to us Nadezhda in the Dark, a novel-in-verse, previously published in the United Kingdom by Footnote Press. We’re deeply grateful to independent presses that make great books accessible to readers across the world. Please support Dzanc Books by ordering your copy today!

When asked to contribute our responses to this book, Yelena Furman said:

“Brimming with references from Russian and Ukrainian literatures to Alla Pugacheva and the Moscow 1990s gay club scene, Nadezhda in the Dark is a poetic disquisition on global history and self-identity. Discussions of Soviet anti-Semitism and the war in Ukraine merge with explorations of immigration and queer love. In language simultaneously lyrical and sharp, Moskovich shows how the personal and political, the present and past, are inextricably linked in ways that are often traumatic but also occasionally hopeful.”

Olga Zilberbourg said: “The Iliad for post-Soviet Jewish dykes . . . Moskovich’s voice commands our attention as it tells – breathlessly, passionately, mixing humor with earnestness – a story about two women whose Soviet roots both unite them and make their relationship impossible. Emotional pitch in this book is turned all the way up! I loved it.”

Dzanc Books and Yelena Moskovich kindly agreed to allow Punctured Lines to publish an excerpt from Nadezhda in the Dark, and we’re delighted to present a passage that refers to a novel we love, Margarita Khemlin’s Klotsvog, available in English translation by Lisa C. Hayden (Columbia UP). Olga reviewed this book for The Common, and we consider it one of the most insightful books about the Soviet Jewish experience(s), written by a woman and centering a female protagonist.

Note: In this excerpt, Nadezhda and Pasha are characters from Nadezhda in the Dark.

* * *

everybody knows

Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and Chekhov, and if you’re bookish

Bulgakov and Gogol and Pasternak,

but

who’s talking about Margarita Khemlin,

who died a handful of years back

and left us with a masterpiece,

Klotsvog,

sometimes at night, when Nadya has already fallen asleep next to me

and the blinds on the slanted window of our bedroom are not fully

shut, I lie on my back and

glimpse the broad nighttime sky,

a dark milky sky,

a pauper’s sky,

a dreamer’s sky,

a prisoner’s sky,

and I think about the sea

and sailors lying in their cots,

like me

except alone,

looking up at a broad nighttime sky,

a dark milky sky,

a doomed sky,

as they think about land,

I won’t ruin the whole story,

but in the beginning, in Klotsvog, the main character, Maya,

—who’s evacuated with her family from the little town of Ostyor in

Ukraine when she’s very little, where the then-thriving Jewish population

is near erased—and skip ahead, the past is the past,

she’s trying it make it in the big city,

but, of course, she falls for the wrong type of guy

and has a baby too young,

a boy named Misha, she can’t raise him

so she sends him to her parents (who are back in Ostyor),

and they take in the boy and raise him on Yiddish instead of Russian

(’cause sometimes when you survive you fall in love with the language

that almost killed you),

some years later, Maya takes Misha back,

she’s horrified that he has learned Yiddish, after all she has done

to rid the boy

of his Jewishness

(bribes and paperwork)

for his own good, damn it, doesn’t he realize, after all that’s happened,

he’s still little, he’s so little,

he’s afraid of the dark, she tells him,

Only speak Russian, he bumbles

words in Yiddish, even though she tells him

Only speak Russian, damn it, he blurts out Yiddish

even in public, she has no choice, she takes

to hard parenting, and, when he cries at night, in the dark,

she doesn’t come

to him unless he speaks Russian,

Only Russian, Misha,

there he is, all alone, all night, whimpering

in Yiddish

in the dark,

our mothers,

our Slavic mothers, our tough-love mamkas,

our beloved mothers, mame ikh hab mura,

muter, muter, Mama, I’m scared,

little by little, Misha learned,

years later,

Maya goes from one husband to another,

gets herself an apartment in Moscow

with a phone

(a luxury of the time),

and her new husband brings in the dough, she’s wearing gold,

gold that Misha, a young man now,

asks how she can wear

gold

from the teeth of Jews, Misha

joins the navy, Maya’s all alone in her big apartment

with her modern phone

and she picks it up

and listens to the dead tone

for company, Misha’s far away with the navy

not because he’s a patriot

or a man’s man, but to get the hell away

from his mama, he lies on his cot

and I’m not sure but I think he looks out

at the dark milky sky

like me,

Misha, my Mishenka,

a grown man now,

on a fleet in the Indian Ocean,

(how attached I get to the people I meet in novels, a Slavic tradition,

we cried more for fictional characters than those

sleeping next to us),

there is a moment, a rare moment,

when Maya is not running around,

shopping or smoothing things over,

in the blankness of one early morning, she wakes up from a dream

where Misha didn’t know how to swim, and he was

afraid,

Nadezhda is resilient,

I don’t know what she’s thinking,

but she could be wondering

if we might try and see, just see if by chance

a cat has braved

the cold,

and snuck up on the roof,

though I know she knows,

as I know,

that it’s too cold for the cats to come on the roof, Nadyenka and I,

we both remember what a piece of candy meant

in our youth,

the whole world stopped at the sweetness on the edges of a child’s

mouth,

Nadezhda is resilient,

but that doesn’t mean it’s enough to make it past thirty

with the will to live,

and that doesn’t mean that we didn’t love life,

God, I loved life, and I think Pasha did too,

even though he didn’t always act like it, he read too much

Tsvetaeva and Akhmatova,

thought of himself like their son,

he had a mom and a pop, but it’s not enough,

people like us,

delicate people, you know,

we need mothers in the form of verse,

God, we loved life, so why

did Pasha’s heart go soft as a peach,

and slimed off at the slightest touch?

Mame,

ikh hab mura,

last weekend, the sun came out in Berlin

and Nadyenka and I decided to celebrate

the lightness of a light sky,

amongst other things,

things we’d rather not say we were celebrating,

like a lift in a bout of regret rolling off Nadya’s tongue

about her ex-wife

and the years of life she had lost,

not just any years

but her late twenties and early thirties, and Nadya kept

repeating herself, then saying it’s all behind her,

and me, I didn’t know what to say,

I hate a woman I don’t know,

and I’m losing patience for the woman I love,

and then we find each other

like we always do, go

to the darkest day of the darkest breath of your darkest word and I

will

still find you,

Nadezhda,

it was a Saturday,

a sunny Saturday,

we sat outside on Karl-Marx-Straße,

me with my heavy leather jacket zipped up, black scarf wound,

a moto-dude silhouette with a 1920s face,

and her, a rose and caramel silk scarf wrapped around her head and

her Masha eyes, as blue as a husky, in her big navy bomber zipped

and puffed,

she’s my Russian Bonnie,

I’m her Ukrainian Clyde, we can see our breath

as we drink our milky coffees

and peck at the black and green olives,

and fork the cured meats with the sliced cucumbers and tomatoes,

and spread jam and honey on chunks we break off the sesame simits,

and nibble at the pistachio pastry that I don’t like, but I nibble anyway,

when you’re in love

you’ll nibble anything,

I clean my palate with the cheese and spinach pirozhki that she lets

me have,

and we usually get a second milky coffee

and have more honey, Nadya loves honey,

I watch her pour it all on her last piece of bread

and it drips and puddles on the white oval plate,

there’s another Yiddish saying, and it goes like this:

Men ken nit ariberloyfn di levone,

You can’t outrun the moon,

Yelena Moskovich is a Ukrainian-born American and French author of four novels. She emigrated from the Soviet Union with her family as Jewish refugees in 1991, then solo to Paris in 2007, and recently back to America. Her writing has been long-listed for the Dylan Thomas Prize, awarded the Galley Beggar Short Story Prize, and named in the Guardian, Telegraph, and Irish Times Books of the Year. She’s written for the Paris Review, Vogue, Times Literary Supplement, and worked for the European Jewish Congress and Yahad-In Unum, as well as taught graduate creative writing at University of Kent Paris School of Arts and Culture.

stas

LikeLike