We’re delighted to welcome Kristina Ten on the blog with an essay about some of the origins—personal, familial, cultural, and political—of her debut short story collection. Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine will be published by Stillhouse Press on October 7, 2025. Please pre-order the book and ask your local and academic libraries to purchase it. Authors and publishers depend on advance orders! And please don’t forget to rate and review.

— Punctured Lines

History Without Guilt

Part of putting a book out into the world is asking people to read it, and part of asking people to read it is letting go of whatever carefully assembled artist statement lives in your head—how you would describe what your work is circling around, grasping at—and embracing that every reader is going to define their experience with your book for themselves.

That’s what I’m currently doing with my debut story collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine. And the definition early readers keep landing on is the word “nostalgic.”

Knowing these readers, I can tell they mean it as a compliment, or at least a helpful neutral statement. All the stories in the book revolve around games and the childlore of the aughts: the divinatory power of cootie catchers, the electrifying lawlessness of the early internet, bonfire legends whispered with a flashlight held under the chin. About half the stories feature young protagonists. Many are set in schoolyards, summer camps, and locker rooms. Others are set in the kind of far-off realms that would feel right at home in a child’s imagination—even as the book itself is unquestionably adult, preoccupied with the horrors of, one, being controlled; and, two, the constant vigilance some of us (girls and women, immigrants, queer people) learn to exercise against it.

So it makes sense, that word “nostalgic.” And still.

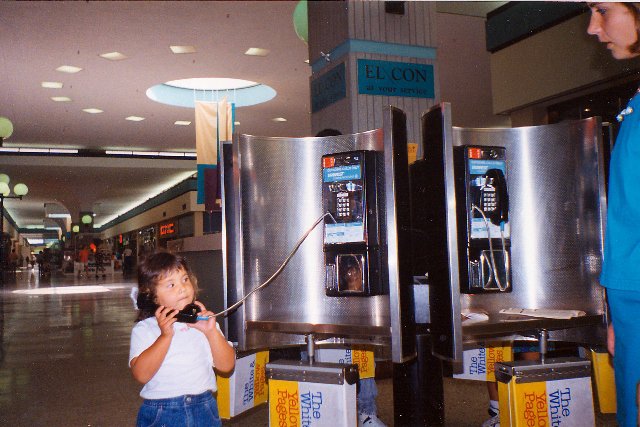

I have a tricky relationship with nostalgia. It’s a complicated thing when you’re a child of empire, more complicated when you’re a child of two. I was born in Moscow to a mother with Siberian roots and a father with Georgian roots, whose own father was one of many Soviet Koreans living on Sakhalin Island before being forcibly deported, under Stalin’s regime, in cattle cars to rural Kazakhstan and other parts of Central Asia (my grandfather was the only one of his siblings to survive this displacement). After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, my parents and I moved to the United States. I grew up in Arizona, then New York, going to summer camp and raising Neopets and marveling at the novelty of AOL Instant Messenger, and I didn’t give much thought then to all the things I write about now: empire, patriarchy, all the terrifying ways a repressive state can assert its power. These days, it seems as though I think of little else.

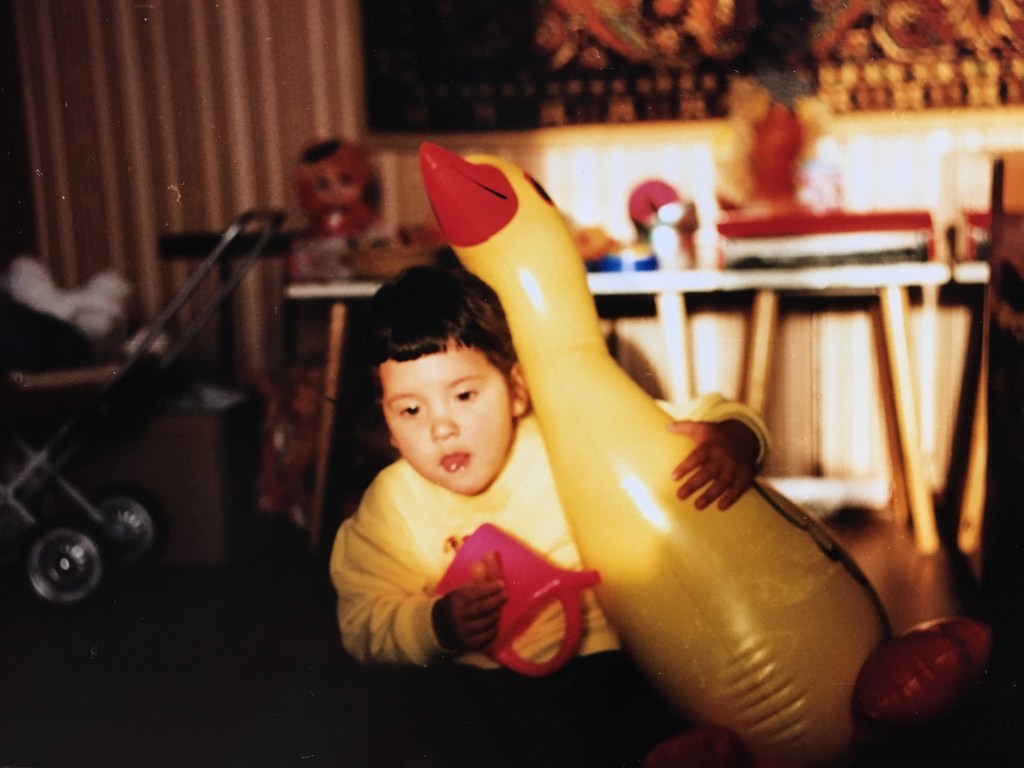

Which isn’t to say I’m immune to nostalgia. I watch those YouTube videos of people who restore vintage Polly Pockets. And whenever my phone surfaces an old photo, “This day ten years ago,” I lose half an hour flipping through the gallery, then start sending pictures to friends with wailing emojis and messages like, “Omg, we were babies!”

All the while, I remind myself that nostalgia is an animal: an unpredictable, shapeshifting creature to be approached with the highest degree of caution. Tempting though it may be to lay a palm on its soft muzzle, I’m too aware of how quickly it can bare its teeth. I’ve witnessed nostalgia used as a tool of the state, in both my home country and my adopted one. I’ve seen it weaponized by authoritarian leaders and their followers to fuel nationalist ideologies, to legitimize expansionist ambitions, to justify war, state-sanctioned violence, and policies that dehumanize and put the most vulnerable populations at risk.

This species of nostalgia relies on a warped glorification of the past, with aims to influence the future. In Russia, it might look like Putin’s reinstatement of the Soviet national anthem in 2000; or, in more recent years, the steady reinstallation of monuments to Joseph Stalin throughout the country, monuments which had been systematically removed starting in the 1950s with the de-Stalinization reforms. In the States, it might look like a longing to return to “simpler, better times,” which, on its face, recalls some idyllic bygone era when it was socially acceptable to ride your bike to a friend’s house without calling first, to knock on their door, ask them to come out and play—and who doesn’t want that? But beneath this rosy vision often churns an undercurrent of traditional values about marriage, childrearing, and the nuclear family, along with anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment.

“Back in my day, we would…”

“Back in my day, we wouldn’t…”

Remember the “good times,” these historical revisionists tell us. Forget the political purges, the labor camps, the cattle cars. Forget the blood-soaked foundation of patriarchy and white supremacy that America is built on, and don’t interrogate who those “simpler, better times” were really simpler and better for. In her multidisciplinary study The Future of Nostalgia, the brilliant Svetlana Boym crystallized it: “Nostalgia is history without guilt.”

I tell myself we won’t be convinced. Or that, even if we are convinced—about our past holding the blueprint for our future; about there being some vague, once-had greatness to return to—when it happens, we won’t be fooled into thinking we wanted it all along. As, in the U.S., hard-gained human rights are stripped, as hard-gained public services and funding for the arts and sciences are dismantled, as public lands lose their hard-gained protections, as hard-gained advancements in healthcare are made inaccessible to millions, as the progress of centuries is undone in the name of some imagined golden era, I tell myself we will not accept this as forward motion instead of the violent regression it is.

Read enough about any nation’s history and nostalgia’s dangerous potential, and it’s easy to get lost in the layers of déjà vu. Add to this that I’m a writer, and that revisiting the past is more or less what I do professionally. To mine it and come up with so much dirt under my fingernails, having forgotten what it is I came looking for.

What I Came Looking For

In the tradition of migration that runs rampant in my family, as an adult I’ve been completely unable to stay still. I left New York for college in Boston, then Boston for a job in San Francisco, then hopped across the Bay to Oakland, which I left for grad school in Chicago, then left Chicago for more grad school in Boulder, then, in an unexpected retreading of ground, recently found myself back in New York State, about two hours from where I went to high school and where my mom still lives.

It wasn’t long before she suggested I come get my childhood books out of her basement.

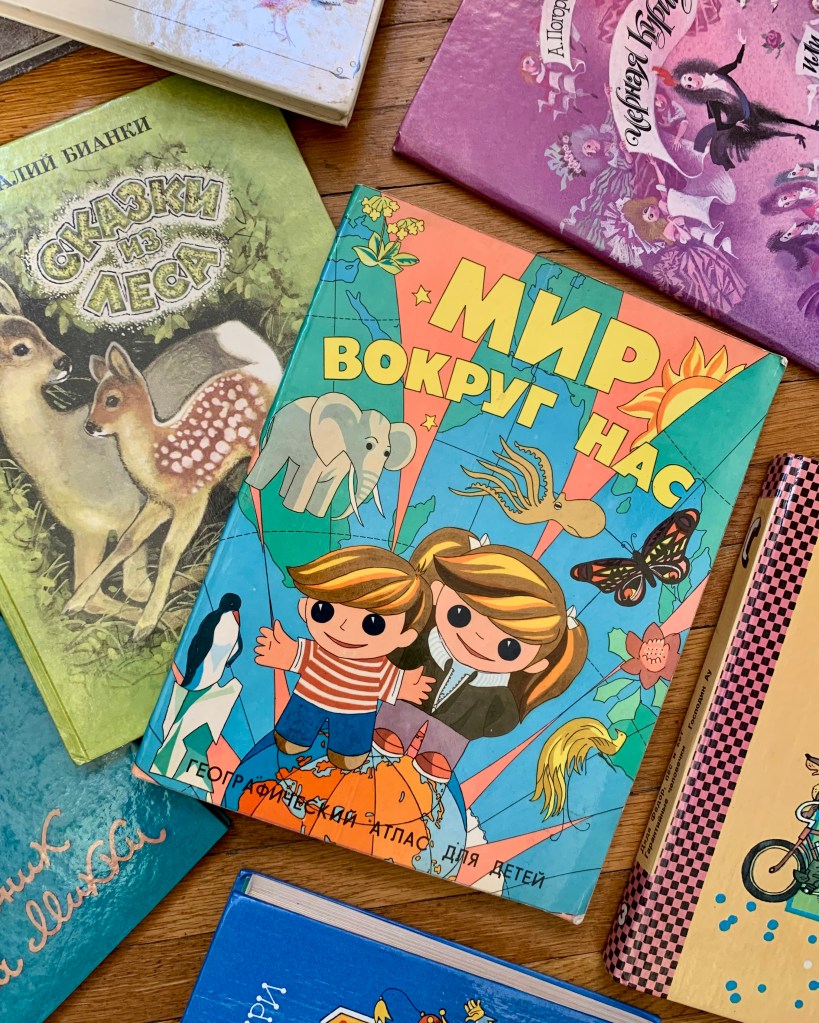

I couldn’t have imagined there would be so many, stacked on metal shelves gathering dust. My parents always talked about me being a voracious reader, and my first favorites were the fairy tales. I was raised on two distinct strains: the Disney classics behind the Little Golden Books’ flashy binding, and the Russian-language skazki my parents had read to me since I was born. These familiar characters sat in my mom’s basement just as they had in my childhood bedroom: Sleeping Beauty and Peter Pan next to Kot Matroskin and Cheburashka, a few with their fragile paper covers torn off, but most looking only a little worse for the wear.

I’d just moved into my new apartment, a two-bedroom rental that, like all my apartments, belonged mostly to the dogs. I wrote in a tiny office that doubled as a workout space, crafting space, music space, and ailing houseplant recovery ward in one corner of the living room. The cross-country move had been painful, with a car that broke down in plumes of smoke on the highway outside Denver, and a Penske my partner and I had insisted (yet again) on packing and unloading without the help of professional movers. A third of the cardboard boxes were marked “Careful! Heavy!!” and filled to the brim with books. Later, sore in muscles we didn’t know we had, we swore we’d never move that many books again.

The acquisition of the hundred-plus children’s books from my mom’s basement wasn’t exactly in keeping with this plan. So naturally I loaded them up, bought the cheapest bookshelf at the Target on the way home, and set them up that day.

Most of the books still live on that shelf. A handful—the ones I remember most fondly—I keep in a fireproof document bag, an artifact of my time living in wildfire country, first in California, then in Colorado. Probably an artifact, too, of some sort of ancestral memory embedded in people of the Soviet diaspora: a resignation to the fact of disaster coming.

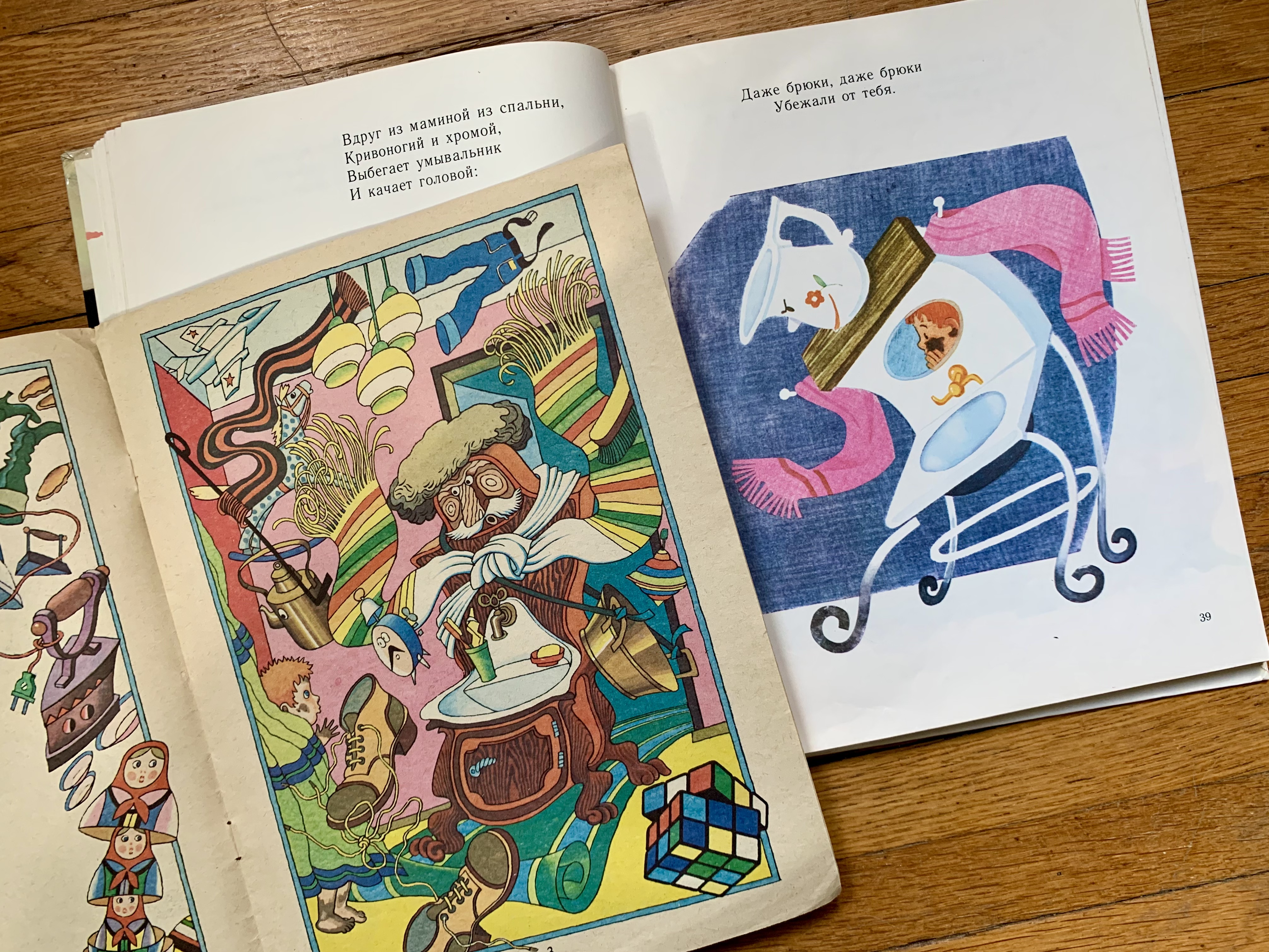

There are picture books for first-time readers amid thicker, glossy hardcovers; stunning, delicate pop-up and pull-tab books; and two versions of the Moydodyr poem—the terrifying story of an anthropomorphized wash basin that lectures a young boy about personal hygiene—the pages aligning almost beat by beat. [PL: The most recent English translation of this poem, by Anna Krushelnitskaya, under the title “Gottascrub,” has appeared in Firefly in a Box: An Anthology of Soviet Kid Lit, published by University of Mississippi Press in 2025.] There are the tales of Baba Yaga, Ded Moroz, Snegurocha, and Tsar Saltan; I’ve written my own retellings of some of these over the years. There are Russian translations of stories I first heard in America, too: Little Red Riding Hood, Pinocchio, The Wizard of Oz.

To justify the sudden increase in our book collection, I told myself these weren’t just decorative objects, another dull succumbence to nostalgia. No, they would be practical. Because, the thing was, these very books were the last ones I read in Russian before enrolling in grade school in the States, at which point I switched entirely to the English-language texts from the local library and Scholastic Book Fair. My Russian didn’t develop past that age, has been stuck there ever since. Meaning these books were at my current reading level. They would be good practice.

Good Practice

Earlier this year, my dad and I decided to visit the country of Georgia, where he lived until he was eighteen and where I lived briefly as a baby, learning to swim in the warm shallows of the Black Sea. It would be part heritage trip, part family vacation; I would see my babushka on my dad’s side—my last living grandparent by blood—for the first time in fourteen years. We wouldn’t go to my dad’s hometown of Sukhumi in the northwest, due to the ongoing conflict between Georgia and the disputed territory of Abkhazia, but would explore the capital of Tbilisi, and the wine and mountain regions to the east.

My dad was amazed by how much Tbilisi had changed since the early eighties, when he traveled there for high-school tennis tournaments. Over a menu featuring khinkali, kharcho, cucumber-tomato salad with walnut dressing, and other Georgian staples, he gestured to the lively, restaurant-lined alley around us and told me that, back then, none of this was there.

My dad and grandma ordered in Russian, and I ordered in English. It was all the same to the server, who spoke both languages, plus Georgian and a bit of Turkish. I could’ve had the exchange in Russian—ordering food is a simple business, and I’d bought a language program before the trip and brushed up by reading the books from my mom’s basement—but I was shy about my accent.

Everywhere we went, my grandma made friends easily, frequently managing to find shared connections to places where she’d once lived or worked. She proudly told anyone who would listen about my forthcoming book. Privately, she asked me about a bio she’d seen online that described me as a “Russian-American writer”—she showed me her phone screen; it was an AI overview. She wondered how that could be, when I write and publish exclusively in English. She said that maybe if I have a book translated to Russian someday, then I’ll be a Russian-American writer.

There are those in America who have their own definitions, I know.

Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine examines this precise in-betweenness. Its central concerns are split identity, self-definition, bodily autonomy, and the possibility of resistance to external forces exerting control. The book investigates what role games and rituals might play in one’s sense of becoming on one hand, and one’s sense of belonging on the other.

And until and unless it’s translated to Russian, my grandma will not know.

After seeing her off to the Russian border north of Stepantsminda, my dad and I did the last leg of the trip on our own. We went first to the famed mineral springs of Borjomi, then to the neighboring Bakuriani, where he’d spent summers at pioneer camp when he was a kid.

Bakuriani is far more built-up now than it was then: a ski town billed as the family- and novice-friendly alternative to the more challenging Gudauri. The sheer number of hotels told us it must be swarmed in winters, but we’d come in July, when it was a virtual ghost town. We took the chairlift to the top of the mountain, just like my dad and his campmates had done more than four decades prior. The landscape was undeniably beautiful: three-hundred-sixty-degree views of lush valleys, miles of wildflowers, peaks tall enough to pierce the clouds. But my dad seemed disappointed by how empty it was. He kept lamenting the condition of the roads, which, it was true, were terrible: so potholed we’d almost had to turn back several times. I tried to console him by insisting that road resurfacing would likely begin in a couple months, in preparation for the high season, though honestly I had no idea. I only wanted to repair his impression of this place, to keep his fond memories intact.

I remembered too late that quote about never meeting your heroes, and thought sacred sites from your youth should come with the same warning.

Then, mercifully, on the way back down the slope, we passed a large group of boys boarding a series of chairlifts heading up. One crossed himself, face blanching at the steep incline. Another elbowed the first playfully in the ribs. I watched something in my dad’s expression ease. These boys could’ve been his age the last time he was in Bakuriani. They could’ve been campmates themselves.

Time folded in on itself like the pages of a pop-up book. I felt a secondhand nostalgia so powerful, it made the thin mountain air go heavy, like rain.

I had wanted an old place to retain its magic, or I had hoped to remake it for my dad until it was the way he needed it to be. But you can’t do that, at least not in real life. Maybe in speculative fiction.

I might be drawn to speculative fiction because reality isn’t enough, and neither is the distorted, falsely sweet reality served up by nostalgia. Both tend to disappoint me. Maybe I write imaginative settings—in this book: an invented authoritarian city-state, an airbus traveling to a sanctuary colony in near space, a version of San Francisco built onto a jousting field—because I don’t trust my memory of real places, nor the memories others would force-feed me. Certainly, this kind of writing offers me a speculative setting in which to try to understand the settings of my own life better: all the places I’ve been but don’t remember well and can’t easily return to. A list that feels too long and keeps on growing.

Every setting in my past feels speculative, in its way. There’s so much I would have to fill in. The khrushchevki and brezhnevki, panel buildings of Moscow, named for the leaders under whom they were built; the four-bedroom San Francisco Victorian into which eleven friends crammed their whole, wild lives (one of us in the closet, another on the roof); the Chicago apartment with deep scratches covering the wood floors, the same girl’s name etched over and over; the Boulder apartment with walls made from pine trees killed en masse by an invasive species of bark beetle…

Don’t these all sound just like fairy tales?

If they do, you understand why my speculative settings feel no more strange to me than the real places I’ve been.

I’ve never quite been able to get my footing: in physical space, in linear time. I’m chronically disoriented. Home, however it’s defined, has no fixed coordinates. And when you’re part of a diaspora whose identity is constantly being shaped and reshaped by political narratives and agendas, slipperiness of the self can become a natural state, too.

Everything slippery. Nothing fixed.

Sounds like speculative fiction.

Kristina Ten’s writing has appeared in The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy, We’re Here: The Best Queer Speculative Fiction, The Best Weird Fiction of the Year, and elsewhere. Along with winning the McSweeney’s Stephen Dixon Award for Short Fiction, the Subjective Chaos Kind of Award, and the F(r)iction Writing Contest, her stories have been finalists for the Shirley Jackson Award and the Locus Award. She is a graduate of Clarion West Writers Workshop and the University of Colorado Boulder’s MFA program in creative writing, and was a 2024 Ragdale writer-in-residence. Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine (Oct. 7, 2025, Stillhouse Press) is her debut collection.

One thought on “We Have to Go Back: Speculative Fiction, Nostalgia, and the Ghosts of Bookshelves Past, Guest Essay by Kristina Ten”