I want to tell you something small, in the great turning of this world, intimate as your grandmother’s soup. When you boil beets, carrots, and potatoes together, the potatoes will soften first, even if they are bigger than the other vegetables.

It is summer 2020, and my hands are Shakespearian (“out, damned spot!”)—beet stained. Our mid-century dining table is a stage set for “Salat Vinegret,” the Soviet-era culinary staple featuring ingredients that are readily available and inexpensive, even in wintertime. The supporting cast of bowls, knives, etc., isn’t from the old country, but is well practiced in recipes that travel back to my early childhood in L’viv, Ukraine.

Beets, carrots, potatoes, boiled and cooled, peeled and diced, are patiently waiting to be mixed with chopped pickles, oil, and sour cabbage. I sigh at the prospect of making this festival dish without the usual bustle of other women around me. Even with my aunts, sister, and cousins helping, this production always tended to run long. “Tedious!” I can almost hear the critical reviews coming in from my 10-year-old self, “a horrible mess!” Now, socially distanced, irrevocably separated from that time and place, I’m near tears with longing for the sweet and sour taste of those memories.

I am making a large bowl of vinegret. Alone. Not for a party. Not for my family.

No one else will see how uniformly I managed to cube the vegetables. Only I will taste the perfectly crunchy and fresh sour cabbage (“kapusta”). I had made it earlier, according to the instructions my mom half-shouted over the phone. “Pozdravlyayu! (Congratulations!) They discovered ‘probiotics!’” Mama had seasoned her explanation of how to salt the cabbage with feigned shock over the health benefits of kapusta and its rich in good gut bacteria brine. Her best cooking wisdom often came with generous side commentary on how out of touch with “elementarnye veshchi” (elementary things) American culture is. “Baba Tanya’s cabbage would make a killing at Whole Foods . . .”

In our adopted hometown of San Diego, empty store shelves and lines at the grocery store are a clunky new accent acquired in the pandemic. For us Soviet Jewish refugees, this is all too familiar. Neighbors are setting up exchanges of flour and sourdough starters. The whole country, in search of comfort, has found its way into the kitchen. We were already there, a strong cup of black tea and sour cherry preserves on hand, in case of unexpected company.

Some way through making the salad (it is taking forever), I turn to another tried and true coping mechanism of not just Soviet, but all troubled times—poetry. Even more readily available and inexpensive, winter or summer, than cabbage, my old passion has asserted itself in recent months as an absolutely essential worker.

Here I am, in my green polka dot apron, with my beet purple hands, writing “Small Work.” In February 2023, it will be the fifth poem in my debut chapbook. Back in 2020, it is a lonely thing, tender and ready to be taken from the pot before any other ingredient. I don’t know why writing it, why making this vinegret, feels so vital and flamboyant. It seems like such a small thing, in the great scheme of things.

Small Work

As a child

trapped at the cutting board

surrounded by boiled, rooted things—beets, potatoes, carrots

longing to be (sprouting, leafing, unearthed)

I didn’t know how fully grown

I would sit at the same task voluntarily

finding solace (meditative transcendence?)

in the easy skill of my well-trained hands

making small work of vegetables under my blade

as if the cutting of soft things

into precise, tiny parts, made everything else manageable

I am following a well-laid path

through soups and salads of my youth

Home tastes just so . . .

my auntie’s praise, a mouthful of pride

“Look how even her cubes of onions are!”

put away and wash, wipe and set the table

—ingredients for not falling apart

When I complained, or tried to rush, my mother

did not say how much it matters to have, if nothing else,

these basic things I can do well

instead, she wrapped my hands around the practical wisdom of a kitchen knife:

“Dochenka,* it is important,

to know how to feed yourself and others”

*Russian endearment for “daughter”

Tea Smells Like Absolution

A cup too hot to drink—boiling amber rich

and heavy as a Tzarina’s dowry

Mine are a pale people who sing

Ochi Chernie (Black Eyes), drink black tea,

greet the New Year at midnight, spin

tales of deep, dark forests, deathless

wizards and endless

cold

Warm yourself by my fire, tell me

what is your comfort food?

Yevgenia

I am hard to pronounce

it’s not just my name, which

used to embarrass me as a child

but now, I don’t mind that

before you get to know me, you have to consider

how your tongue should bend

whether your teeth should click

or your throat constrict

around me

You may want to call me silently, at first

testing out the Cyrillic of my syllables

inside the intimate privacy of your imagination

that’s OK,

I am imagining you too

These poems by Jane Muschenetz appeared in All the Bad Girls Wear Russian Accents (Kelsay Books 2023). “Small Work” originally appeared in MER VOX.

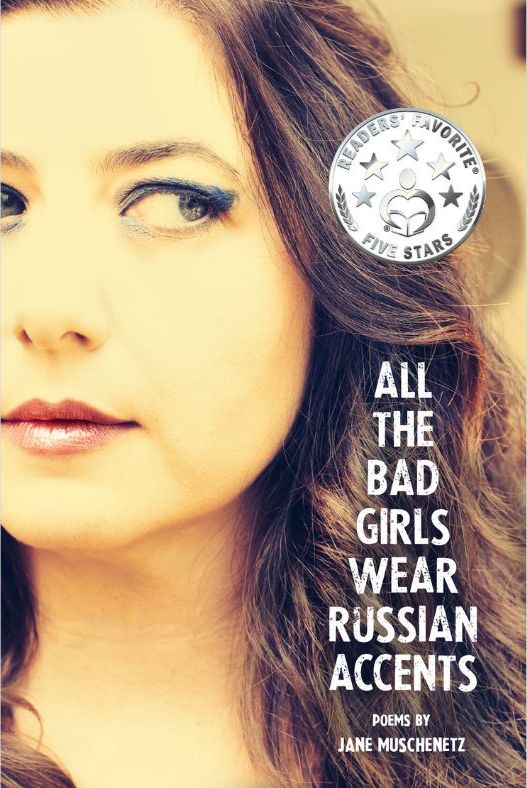

Jane Yevgenia Muschenetz is a Ukrainian-born, Russian-speaking, Jewish refugee who fled the Soviet regime as a child. Recognized for excellence in Poetry Performance by the County of San Diego, Jane is a 2023 City of Encinitas Exhibiting Artist and winner of the 2022 Good Life Review Poetry Prize. Her debut poetry collection, All the Bad Girls Wear Russian Accents (Kelsay Books, 2023), is a Readers’ Favorite 5 Star Book and a finalist for the Jacar Press Chapbook Prize. Jane is also the “butter half” of the husband-and-wife team behind the long-running food and photography blog, Table M. Her second poetry collection, Power Point, is forthcoming in 2024 from Sheila-Na Gig. Connect with Jane’s work at her website www.palmfrondzoo.com.