In the spring of 2007, in St. Petersburg to visit my parents and to promote my first collection of stories, I decided to attend a graduation party of the Gender Studies program at the European University. I’d been a semi-active participant in the Russian-language feminist blogs, where I learned about this program. I contemplated applying; or, at least, since by then I lived in San Francisco, I dreamed about befriending the students and the faculty and making myself useful to them. I had just graduated from a Master’s program in Comparative Literature in San Francisco, where I learned a few things about feminism. I thought my experience could be useful and interesting to my Russian peers. My ideas were somewhat far-fetched.

Established in 1994, European University had the reputation of a progressive institution, focusing on social studies, including history, anthropology, economics, politics. I had never been there before, and I was imagining something akin the American universities that I knew: welcoming signage, flyers everywhere, friendly faces ready to help. I forgot to account for one small thing: my native city’s culture.

The address of European University took me to a grand old palace in the old part of town. The entrance should’ve been obvious, but there were a few young men smoking right outside. Intimidated by the smokers (there was very little smoking on campus in the San Francisco by then) and confused by where one palace ended and another began, I’d walked past the door, before eventually turning around. The smokers–students, presumably there for their exams–stared at me in a way that was evaluative and none too friendly. Once finally inside, I had instructions about where to go, but the instructions simply said “auditorium,” or some such thing; not very descriptive. I remember walking up and down the halls and stairs of this labyrinthine building, feeling very sorry for myself. Did I ask somebody for directions? I can’t remember, but I remember my fear that if I did, the response would be dismissive. “If you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll never get there”–something along these lines. I never made it to the auditorium. I was doomed to being an outsider.

Ok, this was a low moment, but I wasn’t really doomed. The next day, I turned to my aunt Maya for help. She, a librarian, helped me find a bookstore where I could buy the books written by the program’s faculty, and later still I was able to meet some of my LiveJournal friends at cafes and conferences in Russia, Ukraine, in the US. These relationships shaped much of my writing.

Many years later, continuing to lurk on the Russian-language feminist sites, I came across Lida Yusupova’s poem “the center for gender problems” (link to the Russian-language version):

i called an organization by the name of the center for gender problems

could i come to your library

it was January of 1999

i had come back to Russia

from Canada

where i had read a whole lot of books

about feminism

in English

i thought i had a lot of useful knowledge i could share

Though it’s not set in European University, the space that the poet describes is socially and geographically very much adjacent to it (the poem includes a physical address!). I felt absolutely seen by this poem; moreover, the poet had managed to capture and deliver lines I’d been too scared to even fully form in my head: Yusupova’s poem is also about the speaker’s realization that she’s a lesbian and the desire to meet other lesbians. Her words gave me courage and opened a few doors in my mind for me. I became a devotee and sought out Yusupova’s Russian-language book Dead Dad and read everything I could find online.

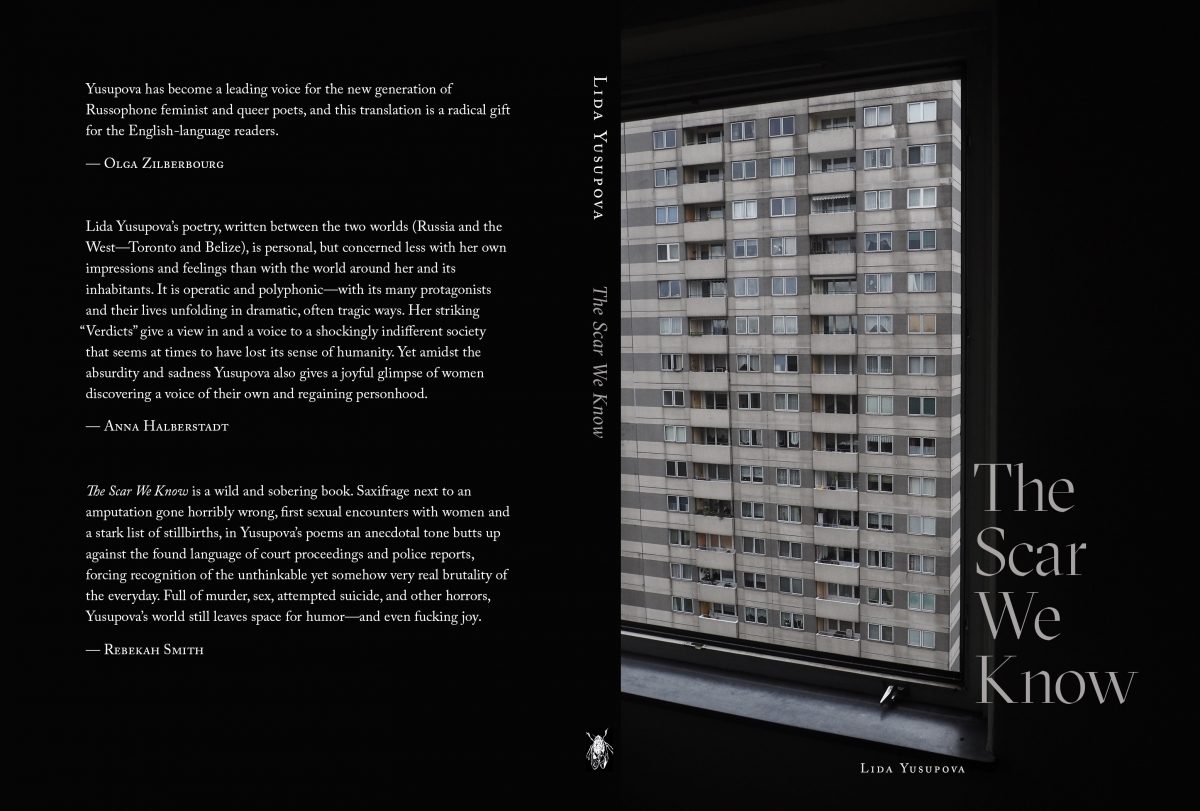

Given the above, you can imagine what an honor it was to be asked to contribute a blurb to Yusupova’s first English-language collection, The Scar We Know, forthcoming from Cicada Press on March 1, 2021. I had to hold myself back from gushing, and nevertheless wrote the three paragraphs below. The editors, advisedly, picked one sentence for the book cover. One benefit of co-editing a feminist blog is that Punctured Lines gives me lots of space to gush…

The “blurb”:

Arriving to the literary scene as the USSR disintegrated into the new Russia, Yusupova gathered her poetic influences both from within and from far outside the mainstream Russian literary tradition. Writing in free verse and relying on line breaks and the blank space of the page for emotional effect, Yusupova anchors her poems in the physical human body. Edited by Ainsley Morse, The Scar We Know is a celebration of Lida Yusupova’s groundbreaking poetry by a community of translators. Madeline Kinkel, Hilah Kohen, Ainsley Morse, Bela Shayevich, Sibelan Forrester, Martha Kelly, Brendan Kiernan, Joseph Schlegel, Stephanie Sandler all contributed to this collection.

The bodies in this book have vaginas and penises, they suffer from dog bites and rape and mental illness and brutal murder, they deliver dead children and alive children that they don’t know what to do with; and they experience occasional bursts of joy, those, too, provoked by the physical bodily sensations: a touch, a look, a good fuck. The poet brings the dead close to us and allows us to grieve for the ways they died, no matter how far away and long ago. Yusupova frequently draws on the language of news reports and court summaries, transforming our relationship with the bureaucratese. In English, her translators juxtapose vocabulary from different registers and patterns of speech and incorporate Russian to insist that the reader looks closely at the subjects of these poems in both their familiarity and uniqueness.

Yusupova has become a leading voice for the new generation of feminist and queer poets in Russia and in the global Russian diaspora, and this translation is a radical gift for the English-language readers, offering us an opportunity to draw deeper connections with the transnational humans who have been marginalized and othered, and to do so while dismantling the accepted patriarchal narratives and systems of value.

Finally, three more links:

In October, Punctured Lines ran a piece about contemporary feminist and queer Russophone poetry, and it included an in-depth interview with Ainsley Morse, the editor and one of the translators of The Scar We Know. Lots more there about Yusupova and the way this book came together.

On January 25, 2021, Globus Books will be holding an online event to celebrate the publication of this book. This event will be held on Zoom at 9.00 am PDT, 12.00 pm EDT and will be streaming on the Globus Books YouTube channel. To register for the Zoom conference, please send a private message to Globus Books Facebook page.

Please preorder and buy the book from Cicada Press or your local bookstore!