Punctured Lines is happy to host a conversation between Ian Ross Singleton, author of Two Big Differences (M-Graphics Publishing, 2021) and Kristina Gorcheva-Newberry, author of The Orchard (Ballantine Books, 2022). The novels’ synopses are below, and you can listen to the writers read excerpts here. Both of these works feature post-/late Soviet space, Ukraine in Two Big Differences and late Soviet/post-Soviet Russia in The Orchard. To support Ukraine in its fight against Russia, you can donate here and here, as well as to several other organizations doing work on the ground. If in addition you would like to support Russian protesters, you can donate for legal help here.

Continue reading ““Writing Fiction Allows Us to Build Bridges”: Ian Ross Singleton and Kristina Gorcheva-Newberry in Conversation”Author: Yelena Furman

The Everyday and Invisible Histories of Women: A Review of Oksana Zabuzhko’s Your Ad Could Go Here by Emma Pratt

We at Punctured Lines are grateful to Emma Pratt for her review of Oksana Zabuzhko’s Your Ad Could Go Here (trans. Nina Murray and others). This review was planned before the war broke out and was delayed, among other things, by my inability to focus on much when it did. I am thankful to Emma for her patience with this process and for bringing Zabuzhko’s work to the attention of our readers. Please donate here to support Ukrainian translators and here to support evacuation and relief efforts.

Continue reading “The Everyday and Invisible Histories of Women: A Review of Oksana Zabuzhko’s Your Ad Could Go Here by Emma Pratt”A Motherland of Books: An Essay by Maria Bloshteyn

Taking your beloved books with you into immigration is intimately familiar to those of us who left the Soviet Union. My parents’ двухсоттомник—”200-volume set”—of Russian and world literature, was quite literally my lifeline to the language and culture that I may have otherwise forgotten, and they are still the editions I turn to today. The covers of the volumes are different colors, and some key moments of my life are associated with them, such as the dark green of Gogol’s Мертвые души (Dead Souls) when I started college. Reading Maria Bloshteyn’s essay was genuinely heart-wrenching, because the experience she describes is that of an acute loss of books that mean so much to us, not just for their content, but perhaps even more so because they have made the immigrants’ journey with us and sustained us in our new homes. In the current moment, this poignant essay is framed by the war in Ukraine, where people like us are losing not just their books, but their lives. If you are able to help, please support translators who are struggling due to the war and this initiative to give Ukrainian-language books to refugee children in Poland. Ukraine’s cultural sphere has been badly damaged by Russian forces, and we will continue to look for ways in which those of us in the West can help. Maria recently participated in the Born in the USSR, Raised in Canada event hosted by Punctured Lines, and you can listen to her read from an essay about reacting to the war in Ukraine while in the diaspora.

Continue reading “A Motherland of Books: An Essay by Maria Bloshteyn”Yevgenia Nayberg’s I Hate Borsch! (Eerdmans, 2022): A Way to Benefit Ukraine

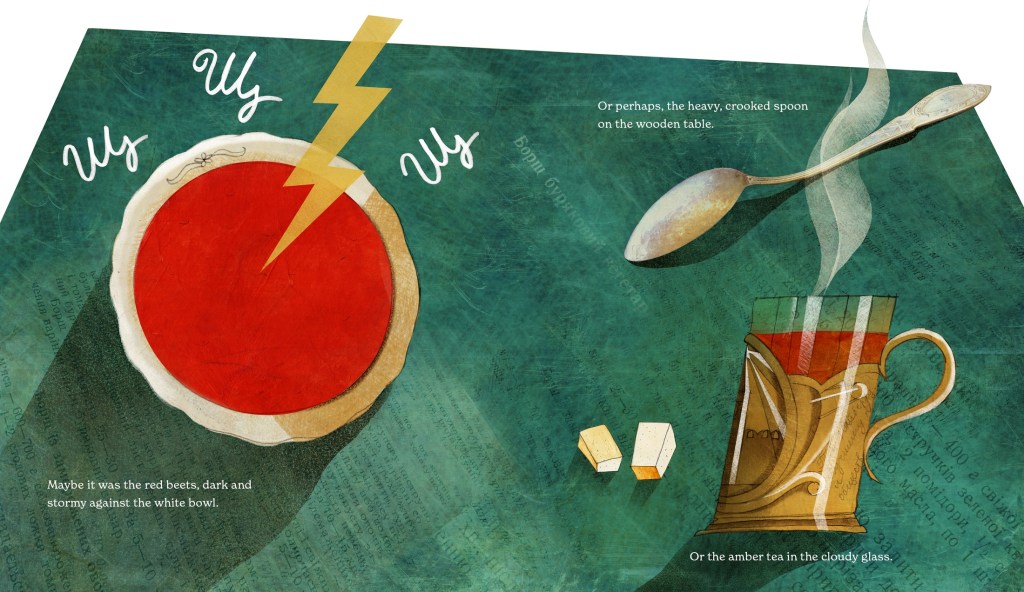

Yevgenia Nayberg is the author and illustrator of several imaginative and visually stunning children’s books. In Anya’s Secret Society, a Russian immigrant girl who loves to draw discovers that, unlike where she came from, being left-handed is perfectly acceptable in America (left-handedness was considered in need of pointed correction in the Soviet Union, as my maternal grandfather could have attested to). Typewriter is the story of, well, a Russian typewriter brought to America and then abandoned by its owner, that finds a new home in the end. I particularly appreciate these children’s books because as far as I know, they’re the only ones that feature immigrant protagonists from the former Soviet Union. Nayberg’s latest book is I Hate Borsch! (what?! Who can possibly hate borsch?!), about a girl who, indeed, can’t stand the stuff but has a change of heart after emigrating from Ukraine to the U.S. The book includes Nayberg’s recipe for the (absolutely delicious) dish. And given several recent Twitter threads in which native Russian speakers expressed dismay at being told that they don’t spell its name correctly in English, I Hate Borsch! spells it exactly as it should be (for fans of Library of Congress transliteration, “borshch” is also acceptable, and no other spellings are).

Continue reading “Yevgenia Nayberg’s I Hate Borsch! (Eerdmans, 2022): A Way to Benefit Ukraine”Donate to Organizations Providing Support for Ukraine

For those watching in horror the atrocities committed by Russian troops in Ukraine and wondering what can be done from afar, here is a list of various types of organizations to support. Given the rapidly developing situation and the number of appeals from various channels, this list is by definition incomplete. If you know of other organizations please add them, and we will be updating, as well. We stand with the citizens of Ukraine, the Russian protesters, and members of the various diasporas who have family, friends, and ties in one or both places.

You Never Know When Speaking Russian Might Come in Handy …: An Essay by Alina Adams

It would be hard to overstate my love of both figure skating and detective fiction, which admittedly isn’t something one normally thinks of together. It is therefore beyond thrilling to feature this personal essay by Alina Adams, who has written a series of five figure skating murder mysteries (yes, really, and I plan to order every one of them). A prolific writer with several fiction and non-fiction titles, Alina’s most recent novel is The Nesting Dolls, which you can read about in the poignant and humor-filled conversation between her and Maria Kuznetsova that Olga recently organized on this blog. I loved reading the story Alina tells below about working as a Russian-speaking figure skating researcher (she must have had a hand in many of the broadcasts that I avidly watched), and I confess to losing, in the best possible way, some of my time to being nostalgically taken back to 1990s figure skating coverage through the two videos in the piece, one of which features Alina translating (for Irina Slutskaya! You all know who she is, right?! Right?!). Let yourself be transported to that marvelous skating era, get ready for all the figure skating at the Olympics next month . . . and watch out, there’s a murderer, or five, on the loose.

Continue reading “You Never Know When Speaking Russian Might Come in Handy …: An Essay by Alina Adams”The Scent of Empires: Channel No. 5 and Red Moscow by Karl Schlögel (trans. Jessica Spengler; Polity, 2021), reviewed by Emily Couch

Punctured Lines is grateful to Emily Couch for her review of Karl Schlögel’s The Scent of Empires: Channel No. 5 and Red Moscow, translated by Jessica Spengler. This book held a particular interest for me because I firmly associate the perfume Red Moscow (Krasnaya Moskva) with my grandmother, who, like many in the Soviet Union, wore this scent. At the same time, I have a memory of standing in a Paris perfumery at the end of my study-abroad program buying a small bottle of Chanel No. 5 to bring back to her as a gift. In one sense, this seems very odd to me, since I can’t remember her wearing perfume in the U.S. and I can’t totally say that I’ve remembered this accurately. But this book and review makes me think I’m right: perhaps my grandmother did like the French perfume because it reminded her of the Soviet one since, as it turns out, there was a connection between them.

Karl Schlögel’s The Scent of Empires: Channel No. 5 and Red Moscow (translated by Jessica Spengler), Review by Emily Couch

I wanted to love The Scent of Empires. When I happened upon it in the flagship Waterstones store in London, I felt a burst of excitement. Here was a book that united many of my personal passions: Russian and French history, fashion, design. The blurb announced that the reader should expect “the interconnected histories of two of the world’s most celebrated perfumes” and “a surprising story of power, intrigue and betrayal.” Yet, unlike the two headline perfumes whose boldly designed bottles represented the revolutionary nature of the scent within, Schlögel’s book does not live up to the promise of its packaging. Despite its diminutive length, The Scent of Empires is not an easy book to distil because it lacks a single essence.

In Chapter 1, Schlögel describes the genesis of the two related scents, charting the trajectories of Ernest Beaux and Auguste Ippolitovich Michel – French perfumers who made their careers in Imperial Russia working for Rallet & Co., purveyor of perfume to the imperial court. Beaux remained with Rallet & Co. until the Russian Revolution in 1917, when he returned to his native France, whereas Michel moved to Brocard, a rival Russian perfumery (which, upon its nationalization became Novaya Zarya). In 1912, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino, Rallet & Co. released the scent “Bouquet de Napoleon,” and both Beaux and Michel took the formula of the “Bouquet” into their post-revolutionary lives. In Beaux’s hands in France, it became Chanel No. 5; in Michel’s in the Soviet Union, it became Red Moscow.

In Chapter 2 the author takes a theoretical turn, examining the place of scent in Western philosophical thought. The Western attitude towards the olfactory, writes Schlögel, was shaped by the Enlightenment, whose thinkers posited smell as “all that is non-conscious, unconscious, non-rational, irrational, uncontrollable, archaic, dangerous.” Despite this antipathy, however, “we cannot simply catapult ourselves out of the realm of scent. We perceive the world not only with our eyes, but also with our nose.” In Chapter 3, he characterizes the Russian Revolution as an event that not only shattered the social pedestal of the elite, but also their sensory world. The smell of cabbage soup, factories, and overcrowded train carriages “breached the walls of the hermetically sealed and orderly olfactory world of the ancien régime.” In the tumultuous years of World War I, the Russian Civil War, and the mass social upheaval that these phenomena entailed, the “odour of the front lines and the bivouac, the sweat of factory work, the stench of overcrowded train carriages – it all forces its way into the perfumed and deodorized realm of high culture.”

Chapter 4 examines how Russia and France – the former through revolution and the latter through World War I – experienced radical breaks with their pasts and dramatic leaps into their own forms of modernity, which manifested itself in fashion and material culture. Schlögel demonstrates how this post-war, post-revolutionary tendency was seen in women’s fashion, drawing parallels between Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel and the leading Soviet couturier, Nadezhda Lamanova, whose designs rejected flounces and adornment in favor of bold, clean lines that allowed freedom of movement to the body. Both “stood for a type of fashion that combined taste and quality and was intended to be accessible even to ordinary people.”

Chapters 5, 6, and 7 outline the cultural and political connections between Russia and France both pre-and post-1918. Chapters 5 and 6 examine the movement of people and ideas between France and Russia. The first highlights how pre-war France was a popular destination for Russia’s elite and dissidents alike: “Paris stood alongside Italy as the most important destination for Russian travellers prior to World War I […] Russian colonies sprang up on the Côte d’Azur in Cannes, San Remo, Antibes, and Nice, and on the Atlantic in Biarritz and Deauville.” Meanwhile, “Paris became a place of exile for Russian revolutionaries […] Revolutionary democrats and oppositionists of all stripes turned Paris […] into a locus of anti-tsarist resistance.” In the second, Schlögel shows how, after the revolution, leading French cultural figures such as Christian Dior, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Le Corbusier, visited the Soviet Union, viewing it as “an ally against capitalism and the impending war.” Chapter 7 pays particular attention to Frenchman Auguste Michel’s rehabilitation by the Soviet authorities, one of the “valuable examples of the Soviet state’s successful deployment of the old intelligentsia,” and his attempts to create perfumes – with names like “1 May” and “Palace of Soviets” to embody the new order.

Schlögel dedicates Chapter 8 to the biographies of Coco Chanel (1883-1971) and Polina Zhemchuzhina (1897-1970), elucidating the unexpected parallels in their life trajectories despite their wildly differing social circumstances. While the general contours of Chanel’s career are likely well-known to the Western reader, those of Zhemchuzhina’s are probably less so. “[F]rom the impoverished environs of the Jewish shtetl” in what is now eastern Ukraine, she rose through the Communist Party ranks until she became the People’s Commissar for the Food Industry in 1939. More well-known to history is the man who became her husband – Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. The chapter is born of good intentions, presenting both Chanel and Zhemchuzhina as “iron women” who made their way in a male-dominated world. The vaguely feminist approach to their biographies is, unfortunately, lost in the somewhat contrived points of comparison between two individuals who, as the author himself admits, “were disparate to the point of antagonism.”

Chanel’s biography contains a somewhat disturbing attempt by the author to excuse her well-documented collaboration with the Nazis: “What the documents do not tell us is whether her activities ever caused anyone great personal harm”. While the book should certainly not attempt to put Chanel on trial for her actions during the occupation, this one-line attempt to brush any criticism of the designer aside is unsettling and detracts from the overall narrative. Schlögel’s account of how the designer used her connections with the Nazi high command to further her business interests – while a well-intentioned attempt to portray her as a strong woman making the best of dire circumstances – is off-putting. In the same vein, Chapter 9’s jarringly brief reflection on the sensory facet of Soviet and Nazi camps brings an unintentional glibness to these horrifying forms of repression and death. “We have the smell of scorched earth and mass graves,” Schlögel luridly writes, “bodies crammed together in deportation trains, pyres of burning books, the smell of the gas piped into the gas chambers and the smoke rising from the crematoria.”

In Chapters 10, 11, and 12, the author ambitiously attempts to cover the nearly seventy years between Stalin’s death and the present day. In Chapter 10 he describes the boom in Soviet consumer culture post-1953, which gave rise to the “Golden Age of Soviet perfumery.” Then, he takes a rather unexpected detour – titled “Excursus,” which appears to be sandwiched between the two chapters –into the life of Olga Chekhova, an actress-cum-cosmetics entrepreneur who founded a perfumery in Munich (not to be confused with her aunt, Olga Knipper, Anton Chekhov’s wife). Schlögel devotes Chapter 11, a mere five pages, to the life of Soviet perfumes in the post-Soviet era. The explosive emergence of Western designer brands after the collapse of the Soviet Union triggered a “reaction against what some viewed as a foreign invasion [that] was not long in coming. Many set off on a search for the lost time that had taken the scents of the Soviet epoch with it.” The revival of Red Moscow, and the proliferation of old Soviet perfume bottles for sale in makeshift markets, symbolized this nostalgia for the recent past. The final chapter, rather oddly, goes back to the early 20th century and the long-unknown foray of avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich into perfume bottle design. In the early 1910s, the artist who would later go on to create the Black Square designed a bottle for the Brocard fragrance – “Severny (North)” – shaped like a polar bear standing atop an iceberg. The design, writes Schlögel, reflected “the spirit of the times” in which nations scrambled to explore and claim the North Pole, “the last remaining terra incognita.” Despite being the premise of the book, Chanel No. 5 and Red Moscow appear as a mere afterthought in the final chapter.

As the above discussion shows, one of the book’s principle flaws is its disjointedness. Instead of a sweeping historical narrative, with the stories of each perfume blended as sublimely as the eponymous scents, Schlögel offers a tale in fits and starts. Just as readers begin to lose themselves in the fascinating, if somewhat hard to follow, origin of the smell that defined two very different societies, they find themselves blown suddenly of course. Chapters 5, 6, 7, and 11, while presenting material of undoubted interest, bear little relation to the story that Schlögel sets out to tell. Chanel No. 5 and Red Moscow scarcely feature in these chapters, which make up a substantial portion of the book. His imagined “museum of fragrances,” in which “Krasnaya Moskva, and even Kazimir Malevich’s polar bear on an iceberg, could take their place alongside Chanel No. 5,” is an intriguing flight of fancy, but there is a distinct sense that the two perfumes on which the work is premised are something of an afterthought, thrown haphazardly into the book’s final sentence to close the narrative circle.

The Scent of Empires is a mere 163 pages, not including the reference and index sections. The readers’ senses have been stimulated, but not satisfied. There is a distinct feeling that much of the story remains untold. It is a shame, for example, that Schlögel does not provide greater insight into his research process. In the prologue, he piques the reader’s curiosity by noting that “[w]hen you rove the bazaars of Russian cities and start collecting bottles […] you encounter amateurs everywhere who have turned themselves into experts,” but this tantalizing sentence remains without follow-up. What kind of Soviet citizen wore Red Moscow? What lives did this state-generated commodity lead after it left the laboratory and reached the apartments of the populace? Now that the scent has been “re-booted” for the post-Soviet era, how has its use and meaning changed? These are just some of the questions which Schlögel leads the reader to ponder but which he leaves unanswered.

The book’s fault lies not in the decision to tell these intertwined stories – even if the connections are, at times, a little contrived – but rather in the superficial treatment that Schlögel gives to them. All this being said, this book is worth reading, containing as it does elements to draw in Russianists, Francophiles, and design aficionados alike and encouraging readers to understand an époque that many believe they know so well through an unexpected medium. The Scent of Empires contains a myriad fascinating notes – the aesthetic embodiment of post-war modernity, Polina Zhemchuzhina’s leading role in the Soviet cosmetics industry, the philosophy of scent – but the author does not quite manage to connect them into a single narrative.

Emily Couch is a Program Consultant for Eurasia at PEN America. Prior to this position, she worked as Program Assistant for Europe at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), where she worked on Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans. She also previously worked at the Kennan Institute, where she regularly organized events featuring high-profile academics, practitioners, and political figures from the region, and frequently wrote blogs and reports on political developments in the region. She holds a double M.A. in Russian and Eastern European studies from University College London and the Higher School of Economics. She is a passionate advocate for fostering greater diversity and inclusion in the Eurasia field, and has spoken on and written about this topic for multiple conferences and platforms, including the Association for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies (ASEEES).

You can purchase the book here and in your favorite independent bookstore. If you are interested in reviewing one of the titles on our Books for Review list, please get in touch at PuncturedLines@gmail.com

Sana Krasikov’s The Patriots: Review by Herb Randall

Herb Randall, whose essay, “A Question in Tchaikovsky Lane,” Punctured Lines was delighted to publish last year, is back with a review of Sana Krasikov‘s monumental novel, The Patriots (Spiegel & Grau, 2017). Krasikov was born in Ukraine, lived in Georgia, and immigrated to the United States; like other contemporary ex-Soviet Jewish writers, she writes in English on Russian/Soviet-related themes. Her first book, the short-story collection One More Year (Spiegel & Grau, 2009), with settings and characters alternating between the U.S. and the former Soviet space, was highly critically acclaimed, and she has won, or been nominated for, several prestigious awards. The Patriots is her second work and first novel, which has also been lauded by critics and readers.

If you are interested in reviewing a title for Punctured Lines, please see our Books for Review and get in touch.

Sana Krasikov, The Patriots, by Herb Randall

…політика — це далі жити в своїй країні.

любити її такою, якою вона є насправді.

політика — це знаходити слова: важкі, єдині

і лагодити все життя небеса несправні.

…politics is to continue living in one’s own country.

to love it as it really is.

politics is to find words: difficult, unique

and to repair one’s whole life this broken heaven.

— Serhiy Zhadan, “Hospitallers” (trans. Maria Kinash for this review)

One question that has troubled humans for generations is how much of a person’s life is determined by the choices they make, and how much by the environment that surrounds them. This tension between free will and external forces like family, society, and history, has been explored in various literary, religious, political, and philosophical works. Sana Krasikov’s The Patriots is notable for its focus on the consequences of an individual’s choices in the face of near-impossible circumstances, and how the consequences affect subsequent generations.

The Patriots is a gripping, often suspenseful read, despite the reader learning key plot elements early as its parallel narratives wind between generations and continents. The novel focuses on Florence Fein, the granddaughter of Jewish emigrants from the Russian Empire to Brooklyn, and her decision to jettison family and country to live in Stalin’s Soviet Union as the ultimate commitment to her socialist ideals. The second plot line concerns Florence’s son Julian and his own son, Lenny, who, as an American, follows a similar journey to Florence to live in post-Soviet Russia. Much of this plot line focuses on Julian’s reflections on his mother’s choices that left him confined to an orphanage and alienated from her even after they are reunited.

Krasikov weaves real historical events throughout her narrative, so readers familiar with the era will appreciate how skillfully she renders the paranoid, conspiratorial milieu at the personal level of her characters, while unobtrusively explaining context for those less familiar with the Soviet Union’s tumultuous history. Florence’s journey from middle-class Flatbush to Soviet life and the Gulag, her clever subversion of the system that imprisons her to save her own life, and her uneasy return with her Soviet-born family to the United States are all so engagingly told that the reader may occasionally yearn for the return to that plot line during the interlacing chapters about Julian and Lenny. These chapters, though, are crucial for a better understanding of Florence’s character and how her decisions impact not only her own life but the subsequent strained relationship with Julian, which in turn affects his connection with Lenny.

Coming of age during the Great Depression, Florence finds a job at the Soviet trade mission in New York thanks to her Russian-language skills. A temporary assignment lands her in the path of Sergey, a handsome young Soviet engineer who is part of a delegation visiting the U.S., on whose account she loses her virginity, and later her job. Left without work, nursing a deep sense of injustice in terms of American society, and feeling trapped in her parents’ home, she looks to the Soviet Union to find “a life of meaning and consequence.” Florence rejects the incremental politics of reform in the U.S. for her own great leap forward. As the narrator says:

Yes, she could have stayed and waited for all the changes to happen— the decades-long march toward progress. She could have stayed and become part of that march. But she’d had no patience for all that. She had wanted to skip past all those prohibitions and obstructions, all the prejudice and correctness, and leap straight into the future. That’s what the Soviet Union had meant to her back then—a place where the future was already being lived. And so she had fled the Land of the Free to feel free.

However, the third-person objective narrator of the Florence chapters makes it evident that she is a master of self-justification. For although her ideals and hopes for the future are her rationale for the decision to live in the Soviet Union, there is another, much more personal motive:

But she was too proud to admit to herself […] a fact that might recast her entire noble journey not by the lantern of courage but by the murkier bed lamp of longing.

Leaving behind her parents, whom she would never see again, Florence severs her connection to America, save for corresponding with her beloved younger brother, Sidney. Florence’s journey across the Atlantic finds her in sympathetic company when she meets another young Jewish woman, Essie, from a decidedly less comfortable upbringing in the Bronx, on her way to Moscow to follow similar ideals. Their friendship lasts for years, until Florence becomes bound to Essie by a moral crisis that engulfs them both.

However, unlike Essie, Florence first lives not in Moscow, but Magnitogorsk. She goes there to search for Sergey, but also as a self-imposed trial by fire to remake herself into a true member of the proletariat, worthy of her new home and hoped-for match. It’s a cleverly chosen detail by Krasikov because it encapsulates Florence’s personality: novelty-seeking, serious, brave, clever, but not as clever as she sometimes thinks. The bustling industrial city being forged there is not the proletariat playground of Katayev’s Time, Forward! Instead, Florence finds chaos, squalid living conditions, indifference from her new compatriots, foreshadowing of political problems, and to her horror, bedbugs. What she doesn’t find is Sergey, who has been forced to relocate to Moscow after complaining about corruption at his workplace.

Florence decides to flee Magnitogorsk for Moscow, where she does finally, very briefly encounter Sergey. It is not the reunion she longs for, and in fact he scolds her for her ill-advised decision to come to the Soviet Union. After his rebuke and rejection, Florence reconnects with Essie and is drawn into her circle of friends, including Leon, another idealistic New York Jewish émigré. Florence is initially repulsed by his brash manner, but gradually falls in love with him and they marry. Florence and Leon adopt the Soviet Union as their home by choice, and the Soviet Union in return abducts them by force.

The realization that she and Leon are trapped in the Soviet Union hits Florence suddenly during the late 1930s at a time of increased prewar tension with America and Europe. She hands over her U.S. passport to a Soviet office clerk while applying for continued residency, and it is never returned despite several attempts to regain it. Leon’s passport is also confiscated. It is only after having lost her passport and reading a letter from her brother that Florence feels an urgent desire to return to the U.S. to visit. Issued a receipt with her passport number and told by the residency office she must renew it at the American embassy, she attempts to do that, but the Soviet police blocking the embassy entrance will not allow her through without the original document. She desperately shouts through the gate but in vain.

Even for those lucky few who manage to pass through the Soviet guards outside, the American embassy is unable and unwilling to help, as Julian subsequently relates:

My parents were hardly the only Americans to be stranded in Moscow after 1936. Hundreds like them were cut adrift in the Soviet Union, comprehending too late that they’d fallen from the grace of the American government. The U.S. Embassy seems to have found every excuse to deny or delay reissuing these citizens their American passports—passports they had lost through no fault other than their naïveté.

Krasikov’s highlighting of this lesser-known aspect of relations between the Soviet Union and America during these years adds further nuance to understanding how little control these expatriates would have over their future after placing themselves in such a precarious position.

Not only is Florence abandoned by the American government in Stalin’s Soviet Union, but, as she later realizes, the Soviet authorities place her under surveillance when she attempts to enter the embassy. She had taken a series of jobs utilizing her native English skills that make her more conspicuous and vulnerable to co-option by the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police. Her handler, Subotin, holds out the possibility that her collaboration will earn her an exit visa. She gradually reveals more information about her colleagues and acquaintances, mistakenly thinking she is manipulating him and keeping her family safe from the terror raging around them. However, like the real-life foreigners who were suddenly trapped in Stalin’s Soviet Union, Florence and Leon, although forcibly turned into Soviet citizens, are still seen as outsiders and therefore suspect by Stalin’s regime.

***

The characters’ outsidedness, in various ways, is a crucial theme in The Patriots. Florence, Leon, Julian, and their friends keenly feel the disconnectedness of multiple identities, of “otherness,” most notably in being Jewish. A child of immigrants in America, an American among Soviets, yet seen everywhere as a Jew, Florence never belongs anywhere entirely, even in the country to which she voluntarily devotes her life:

“Amerikantsi,” Subotin said as he wrote it down. He was smiling to himself, a smile that suggested he knew just as well as Florence did that—American or not— they had the double blessing of being Jews.

During the Second World War, Florence, Leon, Essie, and their friend, Seldon, work for the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, organized by the Soviet government to create propaganda to galvanize political and financial support in the West for the war effort. As victory nears and their usefulness to the regime diminishes, there comes a fresh wave of anti-Jewish sentiment. Florence and Essie recount the sudden rise in antisemitic attitudes even from their close colleagues:

“After all these years, I thought I was finally…”

“One of them,” said Florence.

Essie nodded, her eyes dry now. “But we never will be, will we?”

A generation later, Julian also experiences discrimination, less virulent but still institutionalized in the Soviet Union, when his doctoral thesis is rejected, the quota of Jewish doctorates having already been filled. When necessary to further their aims, the Soviets overlook Florence’s dual identities as “disloyal” Jew and “dangerous” foreigner, while using them as tools to control her, but as Stalin’s regime grows ever more paranoid, she becomes expendable. Florence’s enthusiastic decision to settle in the Soviet Union and devote her life to building communism is not enough to shield her and her family from the midnight knock on the door that all along the reader suspects is coming.

***

Unlike Florence, Julian is a first-person narrator who movingly recounts the story of his abandonment after his parents’ arrests. Spending seven years in a state orphanage, as an adult Julian struggles not so much with that desertion as with Florence’s inability to denounce the system that held them both captive and to admit her mistakes. His yearning to comprehend how Florence could choose to live in Soviet Russia, marry and have a child, while not doing everything possible to protect him is the primary source of momentum in The Patriots, keeping the reader engaged even as the outline of this story is revealed at the outset of the novel. Reflecting on his mother’s actions, he says, “The defining tragedy of my mother’s life was that she’d never had an instinct for family preservation.” When Florence reveals that an old friend had offered them help to flee Moscow and “stay with her relatives for a while, keep low after Papa was arrested,” he is shocked by his mother’s lack of concern for their well being:

“So why didn’t we go?” I said.

But she’d laughed at my dismay. “What was I going to do in a village? Pick turnips? Grow potatoes?”

Compounding Julian’s internal conflict is his adult son, Lenny, who is in Moscow not for any supposed high ideals like Florence, but merely to chase his fortune, precariously and only partially successfully. Julian routinely travels to Russia for business, but he also uses his visits to clumsily try to convince Lenny to return home to America. However, Lenny, who had a special bond with his grandmother, shares her stubbornness:

“Baba Flora didn’t regret her life. And neither do I. She had a front seat on history.”

I thought my jaw might drop. “Is that what she called it?”

“She always said, ‘The only way to learn who you are is to leave home.’”

Like his grandmother, Lenny will not admit defeat regardless of the difficulties. He feels his life in Russia has been an adventure, just as Florence did. Julian, on the other hand, sees only the resulting catastrophe:

“Adventure?” I said. “That’s what they call it when everyone comes back alive. Otherwise it’s called a tragedy. That’s what my father’s life was—a tragedy. And my mother’s, too, for that matter.”

“Yeah? She didn’t seem to think so.”

“That’s because she was a narcissist, Lenny,” I said. “She didn’t think about anybody but herself. She was a grade-A delusional narcissist. Like you.”

The selfishness may have skipped a generation, but Julian must bear the consequences from both mother and son. Just as Florence minimized the many privations and persecutions of her life in the Soviet Union in order to maintain her own fantasy of living with greater meaning there, Lenny is unconcerned about the rough treatment he endures in contemporary Russia and the justified worries of his parents. He is oblivious to both Julian’s childhood traumas and to the fact that, like a child, he still needs his father’s help to escape troubles of his own devising.

***

The catastrophe, when it comes, finds Florence trapped in an impossible moral dilemma, which is largely a product of trying to live in her own idealized image of the Soviet Union. She throws her best friend Essie to the NKVD in a desperate last bid to save herself and her family. However, the net of Stalin’s repressions and paranoia inexorably draws tighter around Florence, her husband, and remaining friends. It is a testament to Krasikov’s skill in creating a truly complex character like Florence that readers will find themselves sometimes sympathizing with her even if she is not entirely sympathetic. They might empathize with her decision to settle in a country with a recent revolution, violence, and state terror in the context of naïve political idealism and the lure of a first romance. However, Florence is unable even decades after her imprisonment in the Gulag to fully admit to herself or her son the extent of the damage she caused by her decision to live in the Soviet Union. Worse still, as Julian points out, the consequences could have been avoided entirely:

“And what about me, Mama? Did you ever think about what would happen to me when they came for you?”

[…]

“Yes, I did think about it. Your father and I talked about it […] [W]e knew that, no matter what happened to either of us, they would never let anything bad happen to the children here. The children were always going to be taken care of.”

[…]

“No matter what happened to you, Mama? […] [B]ut, Mama,” I said, “it didn’t have to happen to you at all! Don’t you get it? None of it had to happen to you, or to anybody.”

Eventually, while in Moscow for work, Julian gains access to his mother’s criminal file that confirms what he already suspected: his mother had been an informer, albeit with the goal of staving off disaster for herself and her family:

[A] victim of her times, of her political beliefs, a victim of her stubbornness and of her illusions. And, certainly, she had been a victim, but until this night I had not considered how she might also have been something else. An accomplice to that very same system that preyed on her. Only now did I allow myself to consider the alternate explanation: that her muteness was not the submissiveness of a slave but the silence of an accessory.

Julian finally realizes that his mother’s inability to renounce her choice to live in the Soviet Union despite the tragic outcome for everyone she cared about was not a rejection of him in favor of her political beliefs. Rather, it was a way for her to deal with the guilt of having been a part of that system of collaboration, denunciations, and betrayals. Tragically, this understanding of her motivations comes too late to repair their strained relationship. Yet Florence unknowingly bequeaths Julian a legacy that brings not only peace to a grieving son, but a way for him to break the generational cycle that he and Lenny are repeating, where now, like Florence’s parents, he is the disapproving father of a child seeking a new life in a foreign country. In her police file, Julian discovers that Florence’s interrogation had ended abruptly, and what could have resulted in a death sentence instead became time in the Gulag with a chance to survive and see her son again. The reason is unclear as Julian reads her file, but Sidney explains how Florence was able to game the system and escape with her life by pitting one of her tormentors against the other. Inspired and impressed by her audacity, Julian uses the same method to extricate Lenny from his legal troubles in Putin’s corrupt Russia. More importantly, Julian comes to understand that, like Florence, full of “[w]anderlust and stubbornness,” Lenny must be left free to follow his own path, even if he feels it is misguided.

***

The final section of The Patriots opens with an abrupt shift to the story of Henry, an American F-86 Sabre pilot in the Korean War, who is downed and ends up in the same camp as Florence, subject to intense interrogation to reveal the secrets of the advanced technology of the fighter jet. Fluent in English, Florence becomes his interpreter, an act that saves her life once again as she uses the circumstances to receive extra rations, rest from physical exertion, and receive necessary medical attention by drawing out the interrogation, with Henry’s cooperation. The pact Henry and Florence make to keep her alive, though, is not entirely sincere on her part. Florence’s symbiosis with the unfortunate pilot highlights the extent to which the life she chose in the Soviet Union results not only in her traumatization by, but her assimilation into, that brutal system. The conclusion of Henry’s story offers a heartrending reflection on the meaning of the novel’s title, as well as a stark personification of the theme of personal responsibility in conflict with the grand sweep of history.

Julian’s uncle advocates the view that the individual is no match for those forces of history that constantly push and pull and sometimes smash:

“The point, my friend,” Sidney said sharply, “is we’re all leashed pretty tightly to the era we’re living through. To the tyranny of our time. Even me. Even you. We’re none of us as free as we’d like to think. I’m not saying it as an excuse. But very few of us can push up against the weight of all that probability. And those that do—who’s to say their lives are any better for it?”

I knew he meant Florence—unpinning herself from one set of circumstances, only to be pinned down by another.

The struggle between fate and free will finds no simple answer in The Patriots. Julian develops a more nuanced understanding of Florence’s tragic life, informed by Sidney’s argument for the inescapability of the system that nearly obliterated their young family. This is not to discount Florence’s responsibility in making her decisions, however: while youthful and naive, they were still hers alone to make. The novel begins with Florence’s creed, “[b]reaking your family’s heart was the price you paid for rescuing your own,” and the enormous, generation-spanning price paid for this outlook lingers in readers’ minds long after reaching the closing pages of Krasikov’s captivating, sensitive work.

Herb Randall lives among the idyllic mountains, forests, and waters of rural New Hampshire and has travelled extensively in Ukraine, Poland, Sweden, and Estonia. He enjoys exploring lesser-known places, reading with a special focus on fiction in translation, and writing about forgotten people and places. His writing can be found in Punctured Lines and Apofenie. Twitter: @herbrandall

You can buy The Patriots here and One More Year here, and of course from your favorite independent bookstore.

“…he cast no shadow in the shimmering silver gloom.” @Muireann @russianlife #WhiteMagic

Back in 2015, when I was on the hunt for every bit of Bulgakov writing in translation that I could find, I stumbled across (and was presented with as Christmas gift!) the marvellous collection of short stories, “Red Spectres”. Translated from the Russian by Muireann Maguire, it’s a wonderful anthology which I loved to bits; so when I found out that she had a new collection out, entitled “White Magic”, I was, needless to say, very interested. Muireann very kindly arranged for a review copy for me, which was absolutely lovely of her, and I’m pleased to report that the new book is just as great as her first anthology!

“Red Spectres” focused on ‘Russian Gothic Tales from the Twentieth Century’, as the subtitle stated; however, “White Magic” takes as its basis writing by émigré authors, and the consistent thread running through the stories is that of…

View original post 875 more words

Pocket Samovar: Interview with Konstantin Kulakov, Founding Editor, by Alex Karsavin

Today Punctured Lines is delighted to feature Alex Karsavin‘s interview with Konstantin Kulakov, Founding Editor of Pocket Samovar, “an international literary magazine dedicated to underrepresented post-Soviet writing, art & diaspora.” A huge thank you to Alex for the initiative to do this interview for the blog and to both Alex and Konstantin for their work on this piece. An equally huge thank you to the editors of Pocket Samovar for creating a space for post-/ex-Soviet writers. Submission guidelines can be found here.

Alex Karsavin: Can you briefly give me the origin story of Pocket Samovar? How did a project that began as a localized conversation between two students at Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School end up involving so many international actors? How did you go about establishing these lines of communication? And finally: how has Pocket Samovar been able to, in a remarkably short spate of time, reach such a dispersed and disparate audience?

Konstantin Kulakov: It started in fall 2019, in Boulder, Colorado at the Jack Kerouac School. It was Kate Shylo, who’s from Yalta, Crimea, me from Russia, and Ryan Onders, who’s from Ohio. Late in the summer, Ryan and I struck a relationship over poetry performance, especially our obsession with Yevtushenko and the orality of Soviet poetry. Shortly, the three of us got together over borscht and spoke about a magazine dedicated specifically to diasporic communities. At first, the word we used was “Eurasia.” Later we realized that “post-Soviet” would be a more accurate term, and we brought it up to Jeffrey Pethybridge, who connected us with Matvei Yankelevich. Matvei was brilliant; he put us in contact with Boris Dralyuk and Eugene Ostashevsky, which ultimately led to the establishment of an advisory board. We didn’t just want this to be a trendy journal that’s translating East European writing. We wanted to highlight underrepresented writers of the post-Soviet space: queer, LGBTQ, Muslim, writers of color, including writers from Transcaucasia, Central Asia, and so on. The hardest part, of course, was to establish these links across time zones, languages, and cultures. Our advisory board proved extremely useful in finding people like Paata Shamugia and Hamid Ismailov. I myself found people like Evgeniy Abdullaev, whose pen-name is Suhbat Aflatuni; he’s based out of Tashkent. It is important to emphasize, for us, the diasporic part of our mission does not center writers in the west; instead, the magazine aspires to be rhizomatic, bridging the gap between North American and Eurasian literary communities.

Alex Karsavin: I was struck by the claim on your site that Pocket Samovar was influenced but not necessarily determined by its editors’ relationship to “Soviet cultural memory.” This is a very rich and arguably fraught territory. Before we go into the particulars, would you mind delving into your (or your colleagues’) relationship to the region at large (be it personal, literary, or academic)?

Konstantin Kulakov: I can only confidently speak for myself. I left Russia when I was 10 years old: a kind of identity rupture or separation at a formative time. And that longing for homeland is really what it’s about for me. The only way I could connect to Russian contemporary literature was online or books. And there was something missing in that, like: Oh, here’s a poem. Here’s an anthology of contemporary Russian poetry by Dalkey Archive Press. And that’s it. I opened the book, and I never felt that it offered me an opportunity to improve my Russian, or to meet Russian people. (Before the pandemic hit we had hopes of actually having events and things of that nature.) So for Kate and me, it really was founded around diasporic longing for a connection to the post-Soviet space, and specifically the kind of literary culture where people can stand up and recite a poem by heart. Living and going to school in Russia as a kid, I hated recitation, because it was required and I wasn’t good at it. In my early childhood, I was moved between Russia, England, and America. I was bilingual and confused, often wonderstruck by language, and maybe that’s why I’m a poet. In many ways, for me, editing this magazine is a return to the language at a time when I feel ready to appreciate it. In Kate’s case, she was born in Yalta and also traveled; she has this nomadic sensibility. I think what interested her was the emphasis on publishing underrepresented voices (particularly feminist and queer). Ryan, of course, came to us via Yevtushenko and translation.

Alex Karsavin: Could you say a bit more about your personal relationship to Soviet cultural memory specifically (given the prominent role it plays in the site’s call for submissions)?

Konstantin Kulakov: Soviet cultural memory. Hmm. I mean, I was born in 1989 in Zaoksky, a town outside of Moscow.

Alex Karsavin: Right at the tipping point …

Konstantin Kulakov: Yeah. I entered a world of collapse, in a state of flux. My memory of that time is mostly of things falling apart and being built up. I actually grew up during the construction of the first Protestant seminary co-founded by my father. So there’s this idea of: “Look! Democracy, religious liberty, international dialogue, etc. are finally coming to Russia!” But at the same time, having been in the United States for 20 years (I’m 31), having experienced individualistic consumerism, there’s now this longing for the samovar, for the communal aspect of poetic memorization and recitation, a longing for something as immense as the stadium poetry of Yevtushenko and Bella Akhmadulina. The longing was also in part a reaction to this feeling among some exiles that Russia is authoritarian, that the arts are neglected or backwards, etc. And something in me always knew the latter was false. I thought: “I know there are poets in Russia and all over the post-Soviet space.”

Alex Karsavin: Why Pocket Samovar for the title? To my mind, the samovar draws obvious connotations to the Tsarist Empire, and nationalism more broadly. Yet, and correct me if I’m off mark, there seems to be a dislocation happening here (even in the simple reimagining of this bulky static object as something miniature and mobile). Am I wrong to interpret this as a sort of queering?

Konstantin Kulakov: There are some things to unpack here. In fact, the mission statement used to be a history of the samovar. It actually emerged in Azerbaijan. The samovar finds archeological origin in the tea drinking devices of Azerbaijan, not Russia. So we were not trying to center the Russian space but rather the region as a whole, its complex, boundary-crossing geography and culture. The communal aspect is also very important. The samovar is circular and presents a spatial situation that is meant to be enjoyed among friends, conversing as equals in a non-hierarchical, free, and spontaneous manner. In the end, we’re trying to be more like a tea room than just a competitive journal that publishes the best of post-Soviet writing. So, if the samovar, something bulky, fits in the pocket, you can definitely say this is a queering; in many ways, the situation of the diasporic writer demands an understanding of fluidity. For us, national identity can change overnight, and language, when queered, affords that fluidity.

Alex Karsavin: Pocket Samovar appears to be the newest in a series of recent publications which take this particular region as their focus (Mumber Mag, Alephi, to some degree Homintern). The magazine is unique, however, in its attempt to put the stateside literary diaspora in communication with its FSU (former Soviet Union — PL) roots. Why is this emphasis on dialogue so important for Pocket Samovar? How does it relate to the magazine’s stated desire (to paraphrase Madina Tlostanova) to reimagine the post-Soviet condition not as a lamentation of lost paradise, but as a way to re-existence?

Konstantin Kulakov: We emerged in Boulder, Colorado, although we are expanding now. One of our editors is in Brooklyn; I might be moving to Brooklyn soon, actually. And then two of our editors are based in Europe, specifically in Luxembourg and in Basel, Switzerland. Daily operation and editorial decisions present new limits and opportunities. So the idea behind Tlostanova’s quote is that we’ve already opened Pandora’s box, so to speak. We can’t go back. Globalization is everywhere. And I think the name “pocket samovar” speaks to that question very concretely. Being in this globalized, fast-paced world, everything is now pocket-sized, everything is mobile, it’s almost like you have to be that way to survive. Ryan Onders, our managing editor, asked me one day: How would the magazine exist physically as a print edition? And I said: It’s a diasporic thing. It’s nomadic. So it has to fit in the pocket, right? That’s when I realized it had to be Pocket Samovar.

The thing is, we can’t go back in time, nor can we escape the Soviet legacy. The “re-existence” Tlostanova speaks of is the ability to create something new and necessary, something that’s based around community in an individualistic and competitive globalized world. For this reason, our new issue emphasized the virtual tea room recordings (of which Stanislava Mogileva‘s was my favorite). We strategically decided to put the video at the top of the page to make it central, and the text secondary. So when you click the link and open the video, there’s this feeling that we’re still honoring that tradition of orality and community, a re-existence of sorts.

Alex Karsavin: Perhaps it’s too early to tell, but what kind of international reception has Pocket Samovar had so far? Also, I want to dive a little deeper into the question of inter-scene dialogue. Given that your contributors represent such disparate literary (and feminist) movements, what kind of exchange (intellectual or affective) have you noticed cropping up in your virtual tea room? Do you think the formal arsenal and thematic concerns of the writers featured in the first issue coalesce into some sort of recognizable whole? Particularly I’m interested in the way writers deal with the theme of dislocation (for example, Stanislava Mogileva appears to recoup the folk song and oral epic genre in the service of Russian feminism, while Elena Georgievskaya queers the biblical language of Revelation).

Konstantin Kulakov: It’s interesting. International communication is definitely happening, even as we speak, on social media. That’s where I’m seeing it and I can’t really talk about the nature of the dialogue yet because we first need to have more events. But it’s generally a sense of excitement that I’m seeing. To borrow a term from Durkheim, it was something of a collective effervescence, albeit virtual. At first, there was this fear among the editors that in calling ourselves post-Soviet, people would freak out and not want to be affiliated with that authoritarian, violent legacy to which we all have our own complicated relationship. However, I think the nature of the post-Soviet space is integrated in such weird ways that there is always literal and discursive travel occurring between the various republics and Russia. For example, Evgeniy Abdullaev is based in Tashkent and has a manifesto called “Tashkent Poets,” but he writes in Russian (not dissimilar to the Soviet-era poet, Bulat Okudzhava, who was of Georgian and Armenian descent). So there’s always this traversing of borders going on. In terms of the response to Pocket Samovar (going off the website traffic), it’s clear that it went completely international. It hit every continent. Because some of the contributors shared it in Azerbaijan, it ended up going all over Central Asia, Transcaucasia, and even to parts of the Middle East, like Afghanistan and Iraq. That, to me, was really encouraging.

It is important to emphasize how literature of the post-Soviet space and literature of the post-Soviet diaspora define the issue. In regards to writing from the region, I would like to highlight Stanislava Mogileva, Elena Georgievskya, Vitaliy Yukhimenko. They are all queer/non-binary poets. Although they have differences, they are united by the similar role sociality, orality, and free verse plays in their work. Learning from these writers and movements–through their work, talks, essays, interviews– is exactly what future issues of Pocket Samovar will be devoted to.

The post-Soviet diasporic writer, on the other hand, finds themselves in a contrasting position to homeland. The post-Soviet diasporic writer may reject their homeland, share an ambivalent attitude to it, adopt a hyphenated identity, or alternate between all of these. Alina Stefanescu’s poetry definitely does not shy away from the brutality of the Soviet experience, but nor does she reject it. “Pickled Plums” celebrates familial traditions illustrating how a planted sapling or thimble of tuica can impart her diasporic life with a sense of safety or vitality of speech. Anatoly Molotkov’s “Poison in the DNA” is aware of the powerful role of the past, but the speaker firmly resists identification with his Russian roots because the roots are “rotten.” However, after reading his poem, “Letting the Past In,” we see Molotkov’s more positive kinship to another Soviet artist: Andrei Tarkovsky. Nonetheless, given the complexities of nationality, our magazine conceives of diaspora very broadly. For example, Steve Nickman’s poetry concerns itself not with land, but with the lives of post-Soviets in the United States. It is too soon to tell, but I can only expect that such literary encounters will continue to demonstrate the need for further exchange and connection, especially given the global challenges we face.

Alex Karsavin: What’s the long-term vision for the magazine?

Konstantin Kulakov: We eventually want to turn the magazine into a nonprofit similar in format to that of Brooklyn Poets. We of course want to grow in funding. We imagine ourselves as a platform for the diasporic community that features poetry and translation workshops, reading events, and conferences. We want to serve as our own social platform, where poets can comment on each other’s published poems. We want to optimize interaction and user experience. The fact is that everything nowadays is becoming more mobile; for example, 60% of the people visiting the website are using phones. At the same time, we don’t want to lose the physicality of a print magazine, of literary evenings (to use a Russian term), which is why our current emphasis is on raising funds for the print issue.

Konstantin Kulakov is a Russian-American poet, educator, and translator born in Zaoksky, former Soviet Union. His debut chapbook, Excavating the Sky, was published by Dialogue Foundation Books (2015). Kulakov is the recipient of the Greg Grummer Poetry Award judged by Brian Teare and holds a Master of Divinity degree from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York. His poems and translations have appeared in Spillway, Phoebe, Harvard Journal of African American Policy, and Loch Raven Review, among others. He is currently an MFA candidate at Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School in Boulder, Colorado and co-founding editor of Pocket Samovar magazine.

Alex Karsavin is a Russian-American literary translator, with translations and writing published in the F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry anthology, PEN America, Columbia Journal, New Inquiry, Sreda, and HOMINTERN magazine. Ilya Danishevsky’s hybrid prose-poetry novel Mannelig v tsepyakh (Mannelig in Chains) forms Alex’s main translation project, a collaboration with veteran Russian-English translator Anne Fisher, funded by the University of Exeter’s RusTrans project. They are currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures at UIUC. They are a 2020 ALTA travel fellow.